Volvo S60 looks hot, drives hot, still safe

NEWBERG, Oregon — Volvo’s long pursuit of safety has been well documented over the years, but less-known is Volvo’s long pursuit of being recognized among the finest European sports sedans. That fact became evident when Volvo introduced the long-awaited S60 to the North American automotive media in mid-September, before the cars reached U.S. showrooms.

Without question, the newest Volvo is the sleekest and sportiest Volvo sedan ever produced, with a strikingly sporty front end and grilled wrapping around its high-tech headlights, and a well-crafted roofline that meets the contemporary standards of being four-door coupe-like. Designed by Orjan Sterner, who was assigned to shape the raciest Volvo in the stable, it will be a big difference after the existing car’s 10-year run. The existing S60 has sold over 600,000, while the new one, built in Ghent, Belgium, is aiming at selling one-third in the U.S., one-third in Europe, and one-third in Asia.

We gathered in suburban Portland, where Volvo officials provided thorough background on the car and its capabilities before we went off on some hard-driving assignments that included hot laps around the road-racing course at Oregon Raceway Park, out near Mount Hood. Before we drove the car, Volvo officials said they anticipated selling it against everything from the Toyota Camry and Honda Accord on up, but its primary targets are the Acura TL, Audi A4, BMW 323 and 335X, the Infiniti G37X, and the Lexus IS-350.

After we had a chance to thoroughly wring out the new S60’s high-powered engine and flat-handling suspension during our day-long driving, the same Volvo officials admitted that its benchmark target was not the Audi A4, but the Audi S4 — the A4’s high-performance specialty car. None of us discounted that lofty ambition, after what we had experienced.

The new S60 has tremendous power, with a, familiar transverse-mounted in-line 6-cylinder engine measuring 3.0 liters of displacement, but internally reinforced and fitted with a twin-scroll turbocharger blowing fuel through 24 valves, activated by dual overhead camshafts. The result is Volvo’s most powerful 6-cylinder engine ever, with 300 horsepower at 5,500 RPMs and a whopping 325 foot-pounds of torque, peaking at 2,100 RPMs and holding that peak until 4,200 RPMs. The driver-adapted 6-speed Geartronic automatic transmission distributes that power to all four wheels.

A new S60 will cost $38,550, on up to $47,050 depending on choices. So intent is Volvo on gaining hot-sedan recognition that it was scarcely mentioned that after the S60 comes to the U.S. in full-out turbo-6 trim, a milder version will become available, equipped with Volvo’s very good inline 5, with or without turbocharging. That version should beat the test car’s 18-city/26-highway fuel economy numbers, even if it won’t match the turbo-6 for performance.

If the look is eye-catching, and the power is definitely Volvo-to-the-highest, the suspension of the car might be its most impressive single feature. Great attention was focused on eliminating the traditional Volvo leaning through sharp cornering. Volvos always have cornered very predictably, and nobody seemed to mind if the slightly stodgy and always-safe Volvos felt as though you might scrape the door handles on the sharpest turns. Nobody, that is, except those trying to compare with an S4, or a Mercedes AMG, or a BMW M3 — the targets Volvo assigned its engineers to catch.

MacPherson struts up front and multilink rear independent suspension both have asymmetricaly mounted coil springs, hydraulic shock absorbers and a stabilizer bar, and the struts have been thickened and the strut mounting stiffness incrased, as are subframe bushings, and the springs are shorter and stiffer. Along with a steering gear’s 10-percent improvement in quickness, the whole package is stiffened by 47 percent. Remarkably, the significantly firmer ride doesn’t ever approach harshness, while delivering vastly improved precision in tracing a curve without a hint of leaning.

The S60 comes with three chassis settings. The Dynamic chassis is standard, and is the same as in European delivery cars, which normally are firmer. The Touring chassis is a no-charge option and is a bit softer. The Four-C — for continuously controlled chassis concept — is an active arrangement with driver-selected choice of Comfort, Sport, or Advanced, and is optional. While the Touring would be the choice for softer coping with rough roads, the greatly stiffened parts of the Dynamic chassis would be the choice for those who like to corner hard. The Four-C, meanwhile, is a technical exercise, with sensors that continously monitor the car’s actions and adjust the dampers in fractions of a second to suit the situation. Engaging Sport mode meant the Geartronic would hold its gear changes longer.

Volvo’s experience with the Haldex all-wheel-drive system fits the latest Haldex perfectly with the steering, suspension and power improvements, and a cornering traction-control system alters the brakes on the inside wheels while adding power to the outside to help you get through a tight turn more effectively.

The race track duty proved the S60’s potential, although I didn’t have my usual enjoyment at Oregon Raceway. The 10-turn track was designed for optimum difficulty, and the designers went overboard to make nearly all the turns blind ones. You speed up a hill, and nothing but memorizing could tip you off to whether it was straight, left, or right on the other side of the crest. I was first in a line of six cars, which meant that all those behind could go hard as possible by keying on the car ahead, but I had nothing to key on, and I only went hard in spurts before letting off on the side of staying on the track. I had far more fun running hard on the curvy highways near Mount Hood on our way to the track.

The S60 is Volvo’s first new car since Ford Motor Company sold the Swedish company to a holding company that also owns Geely Automotive of China. The Chinese financing will help Volvo continue to build its unique cars, and, with a built-in partner, Volvo should rapidly expand its sales success in China. Ford and Volvo helped each other a lot during their relationship, and both seem headed for a prosperous future. For Volvo’s part, that means an unwavering attention to safety. The new S60 underlines that, offering all the proven Volvo concepts, such as lane-departure warning, driver alert control, distance alert, collision warning with full automatic braking, adaptive cruise control with brake assist, and a unique pedestrian detection with full auto brake.

We started our drive in the parking lot, aiming at a small, stuffed, child-size dummy positioned ahead. We were to get up to and hold 20 mph, continuing to steer right at the dummy, without touching the brake. It’s surprising how fast 20 feels as you head for what you’re certain is the inevitable splattering of the little doll, but suddenly — very suddenly, and very close to impact — the brakes are self-activated, hard and right to the point of lockup. And your S60 stops inches short of impact.

A coordinated system that has radar and a camera pointed ahead works seamlessly. The radar in the grille, used also for keeping the adaptive cruise-control space behind a car, detects any object ahead and its distance away; the camera, located on the front facing of the inside rear-view mirror, determines what that object might be. Unbelievable as it sounds, it can detect the swinging of arms or leg motion, comparing it to over 10,000 stored impressions of people, and if it determines that it is a person, the S60 tracks it until you have safely passed. If it steps out in your path as you approach at urban speed, the system will stop the car.

It might drive you crazy in a congested city, or driving through a college campus, where jaywalking seems to be a requisite, because you could find yourself stopping avery 20 feet or so. But Volvo is not joking about such devices. Thomas Broberg, director of Volvo’s amazing safety laboratory in Gothenberg, Sweden, said that in the U.S., 11 percent of all traffic fatalities are pedestrians. Broberg’s focus in recent years has been to keep trying to improve Volvo’s legendary safety, but to strive to find ways to make the driver safer, willing or not.

Volvo started 40 years ago to monitor and compile information from every fatal accident involving a Volvo in Sweden. “We have been able to reduce the risk of fatal crashes in Volvos by 60 percent,” Broberg said, explaining that Volvo also can detect when a driver might be getting sleepy or inattentive, and sound an alert by using the lane-departure technology that sounds if you drift over the dotted line without signaling. “As a driver gets tired, he might drift across the line more, but he also makes more micro-corrections on the steering wheel.”

Keeping the driver alert is a breakthrough in automotive engineering, as is the pedestrian-proof stopping system, which can also help stop the car at any speed when it’s detected to be closing too fast on any object at any speed. At the other end of the spectrum, as we approached the race track in western Oregon, I was second in a group of four S60s when I spotted a small sign that indicated we were supposed to make a 90-degree left turn. The lead car didn’t see it and went straight, as did the third and fourth cars. My reaction, at 60 mph, was sudden as I cranked the steering wheel, and we shot around that corner with incredible precision, and without any leaning.

Amazing that the new S60, which is aimed to take on the hottest-performing midsize cars, is also not about to compromise its intent on building the safest car in its class.

Tony’s ‘curse’ voids Indy 500’s final drama

It was altogether fitting and proper that Dario Franchitti won the 2010 Indianapolis 500. He drove the best race, had the fastest car all day, and might have won a dominant race had it not been for so many yellow caution slowdowns, which force a diminished-speed, single-file order. However, the race was still plagued by the dark cloud that Tony George has forcefully pulled over the legendary Indianapolis Motor Speedway, preventing it from ever attaining the magic it used to have, or the full drama it so richly deserves.

George was in charge back in the 1990s, when the Indy 500 was a fabulous event, the biggest single sports attraction in the world, every year. They would pack 400,000 people into the Speedway, with about 275,000 of them in seats all around the 2.5-mile oval, and the rest partying like crazy in the infield and every other standing-room area available. You had to reserve a room almost a year in advance, and pay a doubled or tripled rate with a three-day minimum, to secure a hotel spot. The whole event took literally an entire month of May to organize, promote, and hold two weekends of qualifying. The first day of qualifying, in fact, might have qualified as the second largest sports attraction in the country every year, because well over 100,000 would show up to watch drivers circle the track one at a time, for four lonely but high-pressure laps.

But because CART, the Championship Auto Racing Teams, had evolved into a far bigger and more popular season series than the old USAC series, CART drivers and teams would take a couple weeks off from their own schedule and come to Indianapolis to dominate the Indy 500. All of the CART races were bigger than all the USAC series except for Indy. So the CART teams wound up having the most clout when it came to rule changes. It didn’t matter how good CART was, the Indy 500 was the biggest race in the world.

When Indy 500 and CART racing were at their pinnacle, Tony decided he was tired of the bigshots from like Roger Penske and Chip Ganassi and a few others coming to the track and dominating the race against the host race teams. Although CART’s rules were more progressive, Tony George rebelled — basically against CART, but also, in a way, against his own institution. He declared new rules that would allow the previous year’s CART cars, but specifically outlawed the already-built new cars. He knew full well that CART teams had sold off their year-old race cars and already built new cars with their costly changes. Tony was right on about one thing — the cost of racing at that level was out of hand.

So Tony George declared his rules, which effectively eliminated the CART teams from participating. CART owners realized they were being locked out, and formed their own 500-mile race on the same weekend as the Indy 500, at Michigan International Speedway in Brooklyn, Mich. Tony whined that CART was boycotting Indy, and some of the lesser-informed media types bought it, so the split became a chasm.

Tony George trumpeted that his Indy Racing League would be for U.S. drivers, driving U.S. cars; for guys who grew up on the Sprint car and other dirt-track ovals. Sounded good, but high-speed racing had gone far beyond that charming, albeit neanderthal, notion. Racing at over 200 mph required the precise touch of drivers who had grown up learning how to race in high-speed go-karts and open-wheel formula cars, not the heavy-handed, rough-hewed guys who could horse a bounding dirt-track sprint car through a four-wheel drift on an oval.

One of those expensive CART rule changes was to reconfigure the cockpit, encircling it with a padded, horseshoe-shaped device around the sides and back of the cockpit. Designed in concert with doctors, the theory was to prevent a driver’s helmeted head from moving far enough in any direction to strike the side or rear of the cockpit in the case of a severe impact. Regardless of the impact, a driver’s head couldn’t snap more than about a half-inch to either side or the rear before it would come up against that cushioned collar. Typically, while the engines and the aerodynamics in the quest for speed got all the headlines, the high cost of making the dangerous sport of 230-mph auto racing as safe as possible.

Carrying out its end of the hassle, CART held its own race at Michigan International Speedway’s oval, on Indy 500 weekend. The 500 had the name and the fame and the history and the tradition, but the Michigan race had more advanced and wealthier teams, faster cars with higher technology, and better drivers. I went to MIS for what should have been a better and more significant race. Once there, I interviewed car-builders and doctors involved in the CART updates for a story I wrote for the Minneapolis Tribune, to disclose the underlying reasons for the cost increases that led to the difference between the two groups.

A botched start prevented CART’s “U.S. 500” from being a huge success. The narrower MIS track meant racers would start in two rows, rather than three. At the start, the two front-row cars got too close together, and neither wanted to give ground. They bumped tires, spun, and caused an enormous chain-reaction crash that wiped out one-third of the field — and all of the positive strokes.

That mess is all that’s remembered from that weekend, but a terrible tragedy before race weekend was the worst situation. Scott Brayton, a Michigan native and the top individual driver left at Indy, was fastest, and won the pole. In practicing for the race, Brayton’s car spun out in Turn 4, and as he fought for control, the car skidded into the outer wall. Brayton died. The official word was that he was killed when his head struck the concrete wall. I was at MIS, but I saw numerous video replays of the crash, which left me shaking my head, because the impact was not that severe, and the car was not that badly damaged. Then I saw one overhead view, which I never saw publicly shown again.

When his car skidded sideways, the overhead view showed Brayton’s helmet snapping severely to the right, about 6-8 inches, and whiplashed back. His helmet never struck the wall, negating first reports that he died of a skull fracture when his head hit the wall. Scott Brayton died of a broken neck because of the severe side-to-side whiplash. In effect, Brayton died because of Tony George’s command that cars racing at Indy would be forced to contain costs, which meant they didn’t consider the updated safety elements CART demanded on its new cars.

That’s a sad story, although very little was made of it. By race day, the media was back to stressing the Indy-CART split, and ridiculing CART for its first-lap crash.

For several years, CART continued to run U.S. 500s, moving to the oval at suburban St. Louis. They ran it on the Saturday when the Indy 500 was on Sunday, so I covered both. I drove to St. Louis, covered the CART 500, then drove late into Indianapolis, where I had a choice of several rooms from whatever motel I stopped at. Gone was the three-day minimum, gone were the inflated rates, and gone was the demand for tickets.

Years later, CART faded, and so did the IRL, but the Indy 500 remained. Some top CART team sponsors informed their teams that they didn’t care about the rest of the season, they only cared that the team race at the Indy 500. Roger Penske went back, playing by IRL rules. So did Chip Ganassi. Those two naturally went on to run the whole season of the newly renamed Indy Racing League, and wound up dominating.

Tony George boasted about having won the war. But what did he win? His basic premise was U.S. drivers from U.S. teams, with U.S. built cars and engines, but the top drivers were coming from Brazil, Europe, Sweden, Canada, and all over the globe. The cars were designed and built in England. The engines were Oldsmobile and Infiniti, and then Chevrolet and Toyota, before Honda, the mainstay in CART, came back to the series too.

Honda engines proved so dominant that Chevrolet and Toyota pulled out of the series. You may or may not have noticed that all 33 cars this year and for the past several years were powered by Honda engines. Nobody blows engines any more, that’s how good the Honda engine technology is. So we have 33 cars that are essentially the same Dallara chassis, running the same Honda engines. It is spec racing at its best — high-tech, but all identical cars and engines. Crowds are a little better, but have not found their way back to making Indy a must-see event.

If you watched the 2010 race, it came extremely close to being the exact sort of fantastic finish that might have caused race fans to rediscover the Indy 500. Franchitti zipped into the lead on the first lap, and he led all the way, yielding only for a few laps when he’d make pit stops, then quickly regain the lead as later-pitting cars came in. Tony Kanaan was a hero, starting 33rd and working his way all the way up to second, and appearing to be Franchitti’s top challenger, along with Helio Castroneves, Franchitti’s top rival. Both Kanaan and Castroneves, however, dropped back before the final laps, needing late pit stops to avoid running out of fuel.

It might have been a humdrum finish, but in the last 20 of 200 laps, a new threat suddenly emerged. Fuel became a problem for Franchitti, too, who was informed by his crew to cool it, to slow down from his 220-mph laps to more like 205 to conserve fuel. He did it, reluctantly, because he had a large lead, and because he knew that if he dashed to the pits for even a splash of fuel, he would blow the lead and the race to Dan Wheldon, who had worked his way up to second, and was closing in. Wheldon’s crew was giving him similar warnings — slow down, or you’ll run out of fuel, but Wheldon said he checked his instruments, and believed he was not in danger, and could have gone harder. He followed his crew’s demands, but he didn’t slow as much, and was still closing in. As the final laps melted away, Wheldon trailed by only the length of the straightaway, and then by less.

As the cars hurtled into their last three laps, the drama was nearing the boiling point. Would Franchitti’s pace be sufficient to hold off Wheldon? If he increased his pace, would he run out of fuel? Would Wheldon also speed up, and did he also face the risk of running out of fuel? Incredibly, Wheldon’s crew stuck by their orders. Had he been turned loose — why protect second place? — I believe he would have overtaken Franchitti, or at least closed in enough to force Franchitti to speed up and run out of fuel.

Coming around to start the last lap around the 2.5-mile oval, the drama was riveting. It was at that precise moment that what we shall call “The Curse of Tony George” struck. Everybody was charging as hard as they dared. Back in the pack, someone named Mike Conway was making up ground, and started to pass someone named Ryan Hunter-Ray, when Hunter-Ray’s car ran out of fuel. When his engine sputtered, Hunter-Ray abruptly slowed, right into the trajectory of the charging Conway. Their cars bumped wheels, and the impact sent Conway’s race car somersaulting over the top of Hunter-Ray’s car and into the outer wall and catch fence. The car did what it was designed to do, disintegrating to absorb impact. Doing that saved Conway’s life, perhaps, although it also scattered chunks of its carbon fiber bodywork all over the track.

Back up front, starting their final lap toward possibly the most dramatic finish in recent Indy history, the yellow caution flag waved and the caution lights flashed all around the oval. Franchitti, clinging to a tiny lead over Wheldon, slowed down immediately, because a caution means single file, with no passing. Conway was lifted out of the wreckage that had been his car, and airlifted to a hospital with a broken leg, but he never lost consciousness.

Franchitti stroked it around the last lap and crossed the finish line, with Wheldon second. Later, Franchitti’s crew said he had 1.6 gallons of fuel left, which was enough to get him around one last lap at reduced speed, but it would NOT have been enough for him to finish at the increased speed he would need to hold off Wheldon. But Wheldon was justifiably frustrated, because his crew found he had more than enough fuel to go hard, as his onboard instruments indicated, and either win the race outright or push Franchitti and win the race when Franchitti ran out of fuel.

Instead of the ultra-drama we viewers had been promised, we were left with the anticlimax of Franchitti cruising slowly to take the checker under yellow. A deserving winner, based on the whole day’s work, but in an outcome that left a few million television viewers drama-deprived and cheated out of a dramatic finish. Tony George has relinquished power at the 500 now, but his presence remains, as The Curse of Tony George.

Range Rover, LR4 sure-footed cliff-dwellers

TELLURIDE, Colo. — “All right, now,” said our Land Rover driving guide. “There’s a jogger coming toward us, so why don’t you stop right here.”

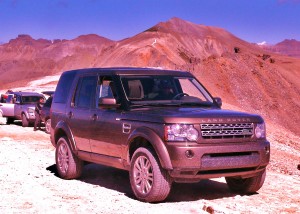

Not a bad idea, since we were just getting started on our unbelievable “Land Rover Colorado Experience 2010” drive, having left our palatial Lumiere Hotel rooms behind, driven into downtown Telluride, which is located at the bottom of a Rocky Mountain canyon, and then our caravan of Land Rover LR4s and Range Rovers turning 90 degrees left off the main street of town, to start driving up from 9,000 feet on something that was described as a county road, but was more a jagged rock-pile formed into a small ledge indenting the side of the San Juan Mountains.

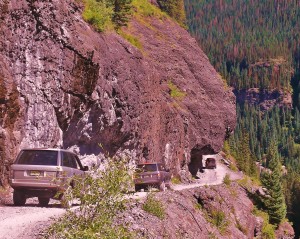

We were divided up, two journalists with — thankfully — an expert off-road driving guide from Land Rover in each vehicle. When they spoke, we acted. So when our guy said stop, I stopped. The jogger — somebody local or else a crazed, high-altitude-overload training fanatic — came slowly along, with a dog on a leash. Stopping allowed the jogger to pass without facing a moving vehicle. It still was testy, because if you looked out our right side windows, you saw we were about 2 feet from a cliff with several hundred feet of sheer drop, and if you looked to the left you saw we had about 2 more feet to a rock wall that reached to the sky.

Our project was a two-day trek. We started in Telluride, which is a town that blossomed from 700 to 4,000 residents when the Rio Grande Southern railroad opened a run from Ridgway in 1870 to service the miners, and then dissolved to near ghost-town status in the 1950s, reviving only as a new and trendy ski-resort town in 1972. The cliffside roads up from Telluride were built to allow gold and silver miners to get to the mines that were dug at random in the mid-1800s. Those roads haven’t been maintained as actual roads since. Aside from the occasional off-road Jeeps and purpose-built specialty trucks and buggies, our caravan of shiny new Range Rovers and LR4s stood out, and as the vehicles soon became less-shiny, they also became much more appreciated by us, because our lives depended on them.

“We have an emotional attachment to this area,” said Finbar McFall, the colorful Irishman who is vice president of marketing for Land Rover/Range Rover. “When Land Rover first came to the U.S., they brought their vehicles to the Great Divide. It was appropriate then, and it’s more appropriate now. This is what our vehicles were made for; they may be made in England, but they were made for here. These are the lightest and most fuel-efficient vehicles we’ve ever made. They are also the most luxurious and most capable vehicles we’ve ever made. Luxurious and capable shouldn’t be compatible, but they are, in these vehicles.”

There were 13 automotive journalists attending the far-out unveiling of the 2011 LR4 and Range Rovers, and all of us knew that when Land Rover holds an introduction, it’s an adventure — whether taking on Utah’s Moab Desert, negotiating a special Land Rover course in Quebec’s Laurentian Mountains, or revisiting the Continental Divide country of highest-altitude Colorado.

These 2011 models are the best vehicles the British company has ever built, although in their 40-year history, they always have been over-engineered for normal use. My experience with them goes back to the 1990s, when they first came to the U.S., but before they became cult-figure vehicles for Hollywood movie celebrities. As soon as I examined and experienced the steel-girder-like frame rails and the lengthy suspension travel, as well as the armor-plating on the underside, I declared that Range Rovers would be the vehicle of choice if you were driving to Hudson Bay — without using roads.

Bob Burns, the headmaster of the group of dedicated off-road experts who work for the company, explained that the 14-day launch in 1990 along the Great Divide was being revisited because, in recent years, the fierce competition among SUVs was focused on-road. “While our vehicles stressed on-road, there never was a penalty for serious off-road use,” said Burns. “But we neglected our off-road capabilities, and a lot of people have gotten away from off-roading.”

Something like 95 percent of SUV buyers don’t ever take their vehicles off-road, but most of those who buy Range Rovers and Land Rovers do, and they are encouraged to take them to the most rugged and challenging sites around the world. Another side to the company’s healthy perspective on off-roading is its “tread lightly” focus on maintaining and keeping off-road areas unspoiled. Even a region as rugged and stunningly beautiful in its desolation as the San Juan Mountain range.

“Every time we go to an off-road area, we know that we have to take care of it, or it will go away,” said Burns. “There are environmental groups who want to close down off-road facilities, but we’ve proven we can leave them in better condition than we find them. We don’t want to damage any part of the environment, but at a place like this, we are driving on roads that haven’t been maintained for 120 years, so we aren’t damaging anything. A lot of people like to hike, but if you hike, you can see only a tiny percentage of what’s here. On this drive, you will see things that very few people in the world will ever see.”

Our route took us up the numerous switchbacks to scale one side of the canyon’s wall. We passed numerous abandoned mines to reach Imogene Pass, which is at 13,000 feet, and continued on the rugged road that was originally created to get through Ute Indian country. We came down into the town of Ouray, and checked into the Beaumont Hotel. We went from the ultramodern, year-and-a-half-old Lumiere Hotel in Telluride, to the Beaumont Hotel in Ouray that had long been abandoned until it was bought and totally restored in 2001. “It’s like a snapshot of the 1800s,” Burns said.

Ouray is a tiny town that was named after the chief of the Tabeguache Utes, who had once rebelled against Indian Agent Nathan Meeker’s attempts to herd them onto a reservation in 1880, as part of swindling them out of their land for the sake of those randomly probed gold and silver mines. All along our trek, the dozens of abandoned mines could easily be spotted by the residue of discolored rocks and gravel hanging like dried teardrops from those holes in the mountain range.

Consider that we drove, except for lunch stops, from 9 a.m. until 7 p.m.for two days, and while we were exhausted from the absolute focus required to pick our way over the smallest choice of boulders, we only covered a total of 80 miles, with no more than 15 of them on real roads. Our vehicles were fortresses designed for such duty.

The LR4 has a base price of $48,500, and in many ways is the more versatile family hauler, because it has three rows of seats to house seven occupants. An enormous sunroof covers virtually the whole top — open-air above the front seats and sunroof above the rear. The Range Rover steadfastly remains a two-row vehicle, uncompromising in its combination of interior luxury, with rich wood and leathers, and audio systems, and rugged, go-anywhere capability. Range Rovers are sometimes bought as status symbols by celebrities, but the company men prefer that those who buy them take them interspers serious off-roading along with the smooth highway cruising.

Range Rovers start at $60,495 for the Sport model, $79,685 for the HSE. Both the LR4 and the Range Rover use the 5.0-liter Jaguar V8, a direct-injected, dual-overhead-camshaft gem with variable valve-timing, turning out identical numbers of 375 horsepower at 6,500 RPMs, and 375 foot-pounds of torque at 3,500 RPMs. That power was more than enough, even for the extremes we confronted and conquered, but if you get the Range Rover, you can choose the supercharged version to boost power from 375 to 510 horses, and from 375 to 461 foot-pounds of torque, a peak that is spread out from 2,500-5,550 RPM, although that adds another $15,000 to those base prices. The LR4 is still the solid, body-on-frame construction with hydroformed, high-grade steel frame components and double-zinc-coated steel body panels, while the new Range Rover has been refined with a one-piece monococque body attached to three steel subframes, for the best of both worlds. The fenders, hood and doors of the Range Rover are aluminum for light weight, and the rest is double-zinc-coated steel.

We had driven an LR4 the first day, so we switched to a Range Rover the next morning, when again we had bright, sunny weather as we drove from Ouray to Silverton, our lunch destination. Later we climbed back up to the top of the world, preparing for a spectacular descent, on Black Bear Pass Road, where we crept down a series of switchbacks that even now, in memory, seem impossible to have attempted. With all that available power, it seems an incredible irony that the best part of both vehicles is their ability to inch down severe, treacherous cliffs.

In either the LR4 or the Range Rover, the console-mounted controls become vital. The ZF 6-speed automatic has command shift that sets to normal, sport or manual, and the permanent 4-wheel drive has 4-wheel electronic traction control, while the 2-speed-transfer allows shifting on the move with an infinite variable lock on the center differential.

Terrain Response is operated by a knob on the console, which can modify the engine, transmission, both differentials, the DSC, as well as the traction control, by which click of the knob you select.One setting is for general roadways, with alternatives for grass-gravel-snow, mud and ruts, sand, and finally to rock crawl. With all of that, you might shift the gear lever into “1,” locking the differential into low range 4×4. Terrain Response modifies the responsiveness of your engine, transmission, both front and rear differentials, the DSC (dynamic stability control) governing active roll mitigation, cornering brake control, and hill descent control. Thank God for hill descent control.

Amazingly, once engaged, you can take your foot off the gas and leave it poised but not riding the brake, and the system causes the big truck to tiptoe down the steepest grade, or pile of rocks and boulders, at something like 1 mile per hour. When we got to the top of Black Bear Pass Road and started our descent, I turned the main knob of Terrain Response to “rock crawl,” made sure we were in low-range lock, and shifted into first gear, as instructed.

Black Bear Pass Road descends from the still-standing hydroelectric station perched on the top of the cliff, next to Bridal Veil Falls, the highest waterfall in Colorado, and the road itself is described as “a treacherous series of one-way switchbacks.” Treacherous? My co-driver and I alternated driving and sitting in the right rear, so our guide could sit in the front passenger seat. Before we got to Black Bear Pass, I heard our guide tell my city-dwelling co-driver: “I want you to concentrate now on being gentle on the gas and hard on the brakes — because right now, you’re doing the opposite.”

My co-driver, however, fell victim to a high-altitude headache on the second day, and said he didn’t feel up to the concentration and would forfeit his turn at driving. That allowed me the combination thrill and relief of driving all the way down that cliff, back to Telluride. As a veteran of successfully scaling the icy avenues of Duluth, MN., in the winter, I was greatly relieved to drive that whole stretch, enjoying the adrenaline high. Extremely focused driving is the easy winner, compared to sitting helplessly in the back.

The cliff where we started our descent is a stark, granite facade, rising 2,400 feet above Telluride, and that thin column of water splashing down the wall nearby is Bridal Veil Falls, the highest waterfall in Colorado. Some of the switchbacks on the rugged and primitive trail are shaped more like a “Z” than an “S,” which means that even with quick steering and an excellent turning radius, there was simply no way to make the turns in one swing. Our guide got out, stood at the precipice, and waved me forward. “More…more…more…” he said.

“You’ve got to be kidding!” I responded, because there was only what remained of 2,400 feet of air visible beyond the hood of the Range Rover. “You’ve got to trust me,” he said. To which, I answered, “Yeah, but you’re out of the vehicle!”

I inched forward until he finally said “stop.” I stopped, and needed no reminder to hold my foot firmly on the brake pedal, then engage the emergency brake, then with my foot still on the brake, shift to reverse. That way, there was no creeping forward, which might have led to something more than “creeping” downward.

When we finally got to the bottom, the caravan stopped to change the right front tire of one of the other Range Rovers. My co-driver seemed miraculously recovered and asked to drive the rest of the way. That was through the town of Telluride and the luxuriously smooth ride on the short stretch of highway we enjoyed back to our Lumiere Hotel. Instantly, it seemed incomprehensible to consider what we had just done. that we had just driven . Never had we driven so long, with riveted focus on every inch of moving up, over, and down, for two full days, yet covering so few total miles.

Land Rover vice president of communications Stuart Schorr said: “Our customers can spend a day on these trails and see sights most people will never see.” We had done exactly that, witnessing sights and sensations that only precious few other humans — beyond the Utes and the miners — will ever see.

The home stretch was the delicate descent by Range Rover, left, and LR4 back to Telluride, far below.

Equus takes wing as luxury-level Hyundai

PALO ALTO, Calif. —The North American introduction of the 2011 Hyundai Equus was well orchestrated, but in a way, I felt like I had cheated. I had gotten a brief, and swift, early sample of the Equus, which was definitely more impressive than anything we could do on the twisting mountain roads near Palo Alto.

A couple of months before the late-August introduction of the Equus in North America, I had the opportunity to visit Korea, ostensibly to try the new Sonata Hybrid and Sonata 2.0 Turbo models at Hyundai’s research and development track. It is a huge layout, with various handling courses, and room for a slalom, acceleration and braking tests, all encircled by a 4-kilometer high-speed oval track. The highest lane on the oval is banked at 43 degrees — steeper than Talladega, if you’re a NASCAR fan.

The plan was to venture onto the high-speed track to try the Sonata with its soon-to-come 2.0-liter turbo engine, so my co-driver and I hustled over to a 2.0 Turbo parked on an escape road halfway down the straightaway on the oval. But a couple of other journalists beat us to the Sonata. There was another car parked there — a long, luxurious sedan, sitting in stately elegance. “Can we take that one out?” I asked the Korean fellow monitoring the one-lap runs of the 2.0 Turbo Sonata.

“Sure,” he said, with a shrug.

I had been thinking that Hyundai might surprise us with a first-look view of the Equus on that trip, but I hadn’t expected to be able to drive it. Especially on a high-speed oval that I didn’t know existed. I jumped at the chance and climbed behind the wheel. We were waved onto the track. Being halfway down the straight and knowing we would only get one lap, I stepped hard on the gas.

New engines, refinement spark 2011 Mustang

My rule of thumb regarding new vehicle introductions is that the hyperbole seems to be inversely proportional to the substance. But while some automakers have compromised reality with hype, Ford might be guilty of understatement with the introduction of the 2011 Mustang.

If you don’t think it looks different, drive one through city traffic and see how many people in other cars, or on foot, shout out and give you a thumbs-up. And if you don’t think it performs differently, then you fail to comprehend the significance of an entirely new and high-tech, all-aluminum, 5.0-liter V8 that tops 400 horsepower and is more “boss” than those fondly remembered Boss 302 engines of 1970. Or, a novel application of the 3.7-liter version of Ford’s high-tech V6 that tops 300 horsepower. Both engines perform admirably for go-power as well as go-past-the-gas-station efficiency.

Summoning the nation’s automotive media to Los Angeles, Ford introduced the new car by officially calling it the “2011 Mustang Refresh.” During a car’s four or five year lifespan, it might get refreshed with a mid-term styling tweak, and in the Mustang’s case, that was done for the 2010 model year. The new 2011 version stayed on the same platform, with the same basic silhouette, and the innovative interior features, so some journalists overlooked the obvious question why Ford would bring a herd of journalists to California for a change of grille and tail fascias. Some published syndicated reports I’ve read expressed positive vibes, but said since the Mustang was revised and refined for 2010, the 2011 is only a modest alteration.

Modest? Ford may have to go back to Hyperbole School.

Chief engineer Dave Pericak simplified the preliminary information by issuing the motto the engineering team accepted as its challenge: “Improve everything, and compromise nothing.”

Car-makers who have done much less to a car could have turned that into a 20-minute monologue.

Ford revolutionized the U.S. auto industry when it brought out the first Mustang, back in 1965, leading a charge that brough us the Chevrolet Camaro, Dodge Challenger, Plymouth Barracuda, Pontiac Firebird, and American Motors the Javelin, as everybody sought a piece of the highly popular “ponycar” segment. Younger journalists, who might not remember all that, have actually written that the term ponycar came from the name Mustang, assuming a horse-to-horse connection, when actually the term covered that whole array of long-hood/short-rear deck, front-engine/rear-drive sporty coupes, because they were smaller than the big horses — larger sedans and sedan-based coupes.

Midsize cars and the demise of the early 1970s hot cars carved into the segment’s chunk, and one by one, all of them disappeared — all but the Mustang, which tried to change with the times. The times saw a Japanese takeover of the sporty coupe market, with Honda leading the way with the Accord’s coupe version, and the expansion of cars such as the Mazda MX-6 version of the 626. So the Mustang got smaller, but it also under-achieved with less-performance, then it grew again, and took on a newer V8 engine. Finally the Mustang came back out resembling its original self, and the resurgence was so successful that Dodge brought out a new Challenger, and Chevrolet followed with the much-promised and long-awaited return of the Camaro.

Ford stayed on its game, refining the Mustang and adding the latest two or three Shelby models to revive memories of Cobras past. The Challenger and the Camaro are stunning to look at, but they share one problem — both are surprisingly heavy. The Challenger body was placed on the Charger’s sedan platform, and stuffing a Hemi V8 in it helped performance. The Camaro is also very heavy, so Chevy complements a strong 3.6-liter V6 with the 6.2-liter Corvette V8. So it moves, and quite well at that.

With an eye toward those two reborn competitors, Ford redid the Mustang’s 2010 refinement to make it lighter and more agile. An adequately powered sporty coupe with its overhead-cam 4.6-liter V8, the Mustang kept clinging to its all-around driveability edge. Still, Chevy both the Camaro and Challenger are attracting attention with lots of power from those large, if aging, pushrod engines.

That prompted Ford to add to its recent surge in technical advancements while upgrading the Mustang again for 2011, installing either its high-tech V6 or an all-new 5.0-liter V8.

First, Ford did away with the aged 4.0-liter V6, an engine that began life powering Ford’s European cars, with a German heritage that gained overhead cams and enough improvements over the years to almost stay contemporary. In the meantime, Ford had built a jewel of a high-tech 3.5-liter V6 three years ago — with a 3.7-liter version as well. Those provide the drivetrains of choice for almost everything in Ford’s stable using transverse-mount, front-wheel-drive architecture.

For the Mustang, Ford engineers switched the 3.7 to longitudinal placement, connected it to a driveshaft, and ran its power through to that solid axle rear.

If you didn’t know there was a V8 available, the 3.7 V6 would be more than enough, even if you are a V8 fancier. Its 305 horsepower puts it in the class of one that can boast of more than 300 horses and an EPA estimate of over 30 miles per gallon, at 31 highway. It also has 280 foot-pounds of torque, giving the Mustang plenty of punch off the line, or as the revs rise to its impressive 7,000-RPM redline.

Select the 3.7 with either the 6-speed manual transmission or the 6-speed automatic, and it comes with dual exhausts, which sound satisfyingly potent.

One event at the introduction was for us to drive various Mustangs out to a large parking lot location where a series of cones outlined a nice, twisty autocross. Stabbing the gas pedal for short straightaway bursts, I was impressed enough with the response to ask a Ford engineer, “Are these V8s?” They were not. All the autocross Mustangs were V6-powered, with a V6 that equals the power that the SVT Mustang V8 churned out in 1999.

Maybe the Mustang doesn’t “need” a V8, but there is what we want vs. what we need. The new 5.0 V8 is definitely something special, from its forged steel crankshaft, to its high-revving potency, and to the wonderful exhaust warble.

This time we stopped at a small regional airport, where Ford had contracted to set up a small dragstrip — an eighth-mile straightaway on one of the runways. We were driving GT models, armed with the new V8. Because of an uneven number of journalists, I had the benefit of being accompanied by Tom Barnes, a Ford engineer. Not only was it a benefit because Barnes was a great source of information, but he’d driven the car enough so instead of the usual driver changes along the route, I got to drive it all, both days.

For those still running on the fumes of 1970, it might seem foolish for Ford to look at the Hemi and the 6.2 Corvette engine in its competitors and build its new V8 to only 5.0-liter displacement. But the old American-car theory that “there’s no substitute for cubic inches” has been blown away by the contemporary answer: “Yes there is — it’s called technology.”

Surprisingly, the Mustang has stayed with a solid rear axle, compared to the sophisticated independent rear axles of virtually all other cars. But if the bottom line is how the car handles, the Mustang’s exploits on the autocross course, as well as while sailing through the curving California foothills, up mountains and down through valleys, is pretty convincing. Besides, the weight-saving fits Mustang’s concept of staying light and agile. That’s another reason why 5-liters is more than enough. With the dual overhead cams twirling, the new V8 cranks out 412 horsepower and 390 foot-pounds of torque.

As everybody lined up to take their turns and get acquainted with the standard drag-racing “Christmas tree” starting lights, I took a warm-up run in a Mustang. All of the Mustangs were equipped with the 6-speed automatics, and you could click the traction-control on or off, depending on whether you wanted to screech the street-radial tires or glue the car to the track for maximum traction.

A couple of flashy Camaros were parked in the left lane, with their Corevette engines and all. I tried one, and cranked off a 9.235-second run, hitting 80.81 miles per hour. It felt very fast, and I was impressed. Then I tried a sequence of different Mustangs, with different rear-axle ratios. My three tries ranged from 8.695 seconds at 85.73 mph, to my personal best of 8.573 seconds at 86.17 mph. It’s not as though the Mustang felt that much swifter, but running over six-tenths of a second quicker, and over 5 mph faster is an enormous difference in a standing-start one-eighth-mile burst. Especially when the swifter time and higher speed were both recorded by 5.0 liters against 6.2 liters.

It was fun, and entertaining, as well as informational. What Ford didn’t bother explaining is that with the dual overhead cams and their higher-revving capability, the Mustang was just starting to reach into the range of its performance sweet spot.

As for sticker price, the V6-powered Mustang has a base price of $23,000, and the V8-loaded GT model starts at $30,000. Those are bargain prices for so much performance technology, because the “modest” upgrades of the 2011 Mustang engines measure almost 100 horsepower more for both V6 and V8 versions, as well as 7-miles-per-gallon fuel economy improvements.

Ford also has hit the mark with packages. The GT gets 19-inch wheels, with either a “billet” grille, or the foglight package, which insets large lights inside the grille. You also get a pedestal spoiler on the rear, and Brembo brakes, as well as upgraded and firmer suspension. The V6 models come in an impressive basic style, or with a Mustang Club of America package, with 18-inch wheels over the standard 17s. The V6 can be bolstered by the stiffer-handling Performance package, adding many of the GT items, including special 19-inch alloy wheels.

If I have a complaint on the slick-steering, high-powered Mustang it’s that Ford has borrowed a page from Chevrolet’s book of tricks by adding the hated skip-shift device. Under the guise of summoning misleading fuel economy numbers for EPA estimates, the device causes the 6-speed shifter to go directly from first to fourth during moderate acceleration. If you go really slow, or hit the gas really hard, it will shift directly from first to second. Previously a nuisance only on the Corvette, and other Corvette-powered vehicles in GM’s line, this device is now a reward for buying the stick-shifting Mustang GT.

Maybe I’m in the distinct minority, but I’m a second-gear lover. I don’t want to do standing-start burnouts; I tend to start up moderately in first, then hit second and hammer it a bit. Nothing illegal, mind you, but running up the revs in second is all the kicks I need. When I do my thing on the Mustang GT, I pull the shifter back and hammer the gas…and the thing falls on its face, because I’m in fourth. By the time I’ve wrestled the shifter back up and around and down into second, I’m seething at having lost the thrill of a smooth-shifting upshift into the wide power band.

It’s reason enough to buy the 2011 Mustang with the automatic, which is also a 6-speed, except for one thing: Ford neglected to include steering wheel paddles to allow a driver to manually override the automatic. It’s as if Ford made a boardroom decision to make the new Mustangs really neat looking, and really fun to drive, but cheated everyone out of the fun of shifting.

If the transmissions have the only things I consider less than ideal, the handling certainly is up to the best high-performance standards. The entire platform is reinforced by a large cross-member that aids stability, and the car responds precisely, and steering is razor-sharp. Electric power steering avoids the usual pitfall of numbness, and instead feels well-weighted, while the car gains the asset of not having the weight of a power-steering pump.

The 2011 Mustang also has the optional SYNC system Ford has worked out with Microsoft, allowing occupants to command their personal listening devices around with voice commands. A neat feature that might be seen as a gimmick by many is the ability to alter the instrument lighting and the ambient lighting by changing color at the touch of a button. Do you like red, blue, green, purple, orange, or what? Hit the switch and change it — by the hour, if you so choose.

Cynics who are looking for nitpicks might point out that the rear seat is useful for very small children at best. I don’t see it as a problem. If nobody is riding back there, you just have fewer witnesses to compromise the light weight of the package. Or to hear you grumbling about the blasted skip-shift.

John Gilbert is a lifetime Minnesotan and career journalist, specializing in cars and sports during and since spending 30 years at the Minneapolis Tribune, now the Star Tribune. More recently, he has continued translating the high-tech world of autos and sharing his passionate insights as a freelance writer/photographer/broadcaster. A member of the prestigious North American Car and Truck of the Year jury since 1993. John can be heard Monday-Friday from 9-11am on 610 KDAL(www.kdal610.com) on the "John Gilbert Show," and writes a column in the Duluth Reader.

John Gilbert is a lifetime Minnesotan and career journalist, specializing in cars and sports during and since spending 30 years at the Minneapolis Tribune, now the Star Tribune. More recently, he has continued translating the high-tech world of autos and sharing his passionate insights as a freelance writer/photographer/broadcaster. A member of the prestigious North American Car and Truck of the Year jury since 1993. John can be heard Monday-Friday from 9-11am on 610 KDAL(www.kdal610.com) on the "John Gilbert Show," and writes a column in the Duluth Reader.