Cruze helps Chevy gain small-car focus

By John Gilbert

WASHINGTON, D.C. — The new Chevrolet Cruze made its official media introduction in and around Washington, D.C., and rural Virginia — a setting filled with history and imagery that rivaled the vehicle itself as an attraction. We drove up to the Manassas battlefield, where the bloodiest of Civil War battles occured, and past Bull Run and other historic sites in the Virginia countryside. Until you visit those places, the U.S. capitol emerging in Washington, D.C., while the Confederate capitol was in Richmond, Va., was among obscure memories from high school history class. Visiting them, and their proximity, adds perspective to it all.

That scene plays out as the historical impact of Chevrolet seeking to enliven the second have of its hope to be known as the “once and future” vanguard of the U.S. auto industry, because the Cruze is the vehicle that could prove Chevrolet can, indeed, build an outstanding compact car.

Chevrolet small-car marketing director Margared Brooks told the assembled auto-writers: “We have to bring out cars the people want.”

My personal imagery gong sounded immediately, loud and clear, because during those decades when General Motors made ever-larger and ever-more profitable cars and SUVs, journalists might ask about the social or environment responsibility of building excessively large vehicles with excessively low fuel economy. Every time, a GM executive would shrug and say: “We’re only making the vehicles that the people want.”

We will write off the familiar rhetoric as unfortunate coincidence, because this time it seems that Chevy folks might mean it, and they might finally have caught on to what dozens of warning signs had tried to indicate over the last two decades.

With the Cruze, Chevrolet has something that fulfills U.S. drivers’ wants and needs, and also could represent a large turnabout for responsibility. In the past, GM, and particularly Chevrolet, had such a hold on the industry that U.S. car-buyers would “want” anything Chevy was going to build. But over the last three years, GM has undergone the turmoil of nearly sinking when high fuel costs signalled the abrupt end of large-truck and car sales, which was followed swiftly by bankruptcy, the well-publicized government bailout loans, and only now the apparent righting of the sinking corporate ship.

The Cruze is capable of leaving those cynical memories behind. It is a compact car aimed at challenging the Honda Civic, Toyota Corolla, Volkswagen Golf, Ford Focus, and Hyundai Elantra in a highly competitive downsized market where Chevrolet has been just a token performer. There was the Cavalier, of course, and more recently the Cobalt. Remember, in fact, a few months ago, when football analyst Howie Long exchanged his integrity for a pile of Chevy advertising money, and he’d come on television to announce that the 2010 Cobalt was “better than” the Honda Civic? Howie didn’t tell us that the Cobalt was so good, GM was about to eliminate it for 2011.

The Cruze not only replaces the Cobalt with a slightly larger and more technically advanced car, but from its appearance, ride, handling, and performance standpoints, the Cruze seems to be on-target to be the best small car Chevrolet has ever offered to the public.

A few years ago, when the Saturn Aura was introduced, I suggested it might be the best sedan in the entire GM stable. There was a reason for that. The Aura was a revised version of the four-year-old Opel Vectra from GM’s arm in Germany. A year later, the Malibu was another version of the Vectra/Aura. Then GM blessed Saturn with the Astra, which was a rebadged version of the Opel Astra, and I wrote that car was the best small car GM had ever offered. As GM chose to eliminate Saturn and Pontiac from the scene, Opel had redesigned the Vectra into a new car called the Insignia. With Saturn gone, GM gave the new version of the Insignia to Buick as the 2011 Buick Regal.

Opel, meanwhile, totally revised the Astra two years ago, and it won 2010 European Car of the Year awards. That car and the Cruze share the same platform, with the Astra being a hatchback and the Cruze getting what Chevrolet calls “more expressive” styling. For power it has either a 1.8-liter 4-cylinder in the base LS, or a 1.4-liter turbocharged engine, standard in the LT1, LT2, LTZ, and Eco models. With either a 6-speed manual or a 6-speed automatic, the 1.4 turbo produces 138 horsepower and 148 foot-pounds of torque.

Driving the Cruze is impressive, with its flat and stable attitude in turns, and power that might best be described as adequate. Chevrolet says the Cruze accelerates 0-60 in 10.0 seconds, while the Civic does it in 8.6 and the Corolla in 9.4. It feels composed and coordinated, though, and I prefered the more basic interior styling, with a 2LT model having a coarse woven fabric on the dashboard and for accents.

“The trend is moving away from larger to smaller vehicles,” Our Ms. Brooks said. “Two or three years ago, selling small vehicles was an uphill climb, but in 2008, the spiked fuel prices triggered the move to smaller vehicles. But customers still want upscale smaller cars. If a vehicle is high-styled and more fuel-efficient, customers are much more likely to consider it.”

The design of the Cruze is smooth and contemporary. “It has an exterior to fall in love with, and an interior to live with,” said Michael Simcoe, executive director of Chevrolet design. Among the interior refinements are a contemporary instrument layout, with piano-black and silver trim, a Pioneer 9-speaker audio system, all the Bluetooth and USB connectivity you might want, and even a navigation screen. A nav screen is not to be trifled with. When the Malibu came out and won Car of the Year honors, you could not get a nav screen in the car, but only OnStar’s “turn-by-turn” nav lady telling you where to go. So to speak. There are also safety amenities, such as standard StabiliTrak, traction control and antilock brakes, and inside, there are 10 standard airbags, including front seat side, head-curtain, knee and outboard rear side bags.

Interior volume of the 4-door sedan Cruze shows 94.6 cubic feet of volume, compared to 92.0 for the Corolla and 90.9 for the Civic, and cargo capacity of 15.4 in the Cruze, better than the 12.3 cubic feet in the Corolla, or 12.0 in the Civic. The suspension is excellent, with MacPherson strut front and a Z-link rear with a torsion beam, set up for side-to-side wheel control, making the Cruze handle well enough to potentially handle the competition. The basic Cruze comes with 16-inch wheels and a Touring suspension, with disc front and drum rear brakes. The Sport suspension option adds 17-inch wheels and 4-wheel discs, while the top LTZ has Sport suspension standard and 18-inch wheels. The Sport suspension in the LTZ has higher spring rates than the outgoing Cobalt SS, which is reflected by the car’s superior stability and firmness.

The power, however, is another matter. And the never-ending compromise blending power and fuel economy is the larger part of that question. The 1.8 non-turbo has 138 horsepower and 123 foot-pounds of torque, while the 1.4 turbo has the same 138 horses at 4,900 RPMs, and much stronger 148 foot-pounds of torque which rise to a peak at 1,850 RPMs and holds that peak to 5,000 revs. That engine is part of the recharging system for the upcoming plug-in electric Volt. Its high-tech features include solid cast crankshaft, integrated turbocharger, cast-iron engine block, but requiring no balance shafts, and chain-driven dual-overhead camshafts.

Offering a lot of upscale features, such as impressive sound-deadening inside, are reflected in the Cruze sticker prices. The base LS starts at $16,995, the 1 LT $18,895, the Eco at the same $18,895, the 2 LT at $21,395, and the top LTZ at $23,695.

Chevrolet’s intention to make the Cruze a high-level compact will find considerable competition, because virtually every competitive company is doing the same with compacts. Chevrolet officials are enthused because the lighter, slimmed-down Eco model is aimed at attaining 40 miles per gallon. Ford, on the other hand, hasn’t introduced the new Focus global car yet, and Ford has its smaller Fiesta out and attracting major interest. The Fiesta is smaller than the Cruze, but with surprising interior room, plenty of pep, and over-40 miles per gallon, it also has a lower price tag.

Forget the competition, though. The Cruze sets new standards for Chevrolet, and General Motors. And that’s a tall order for a compact car.

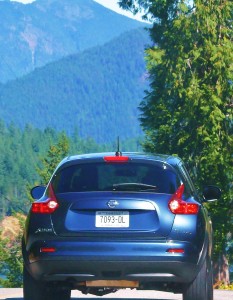

Nissan Juke could…go…all…the…way

VANCOUVER, British Columbia — Imagine a wild party being conducted at Nissan’s design studio, where people from every cubicle choose up sides and play “spin the concept” — in which every participant tosses an ingredient from crossover SUVs, sports cars, compact and subcompact designs and features into a blender. Puree the whole thing, then shake well, and pour out a unique vehicle. Allow it to harden, then squash it down to a size small enough to start a new segment.

Call it “sport-crossover-hatchback-runabout.” Nissan calls it the “Juke.”

Football season is a great time to introduce a car with that name. Fans might appreciate the analogy most, because while some prefer watching a skilled passing attack from someone like Brett Favre, others might prefer the running game, the way Adrian Peterson rushes. When the Minnesota Vikings move the ball, Favre simply hands off to Peterson, who runs through the line with force, feinting an instant one way, then darting the other, all in a split second. That ability, which is nearly impossible for opponents to defend, is called a “juke” in football jargon.

Capitalize the NFL’s slang term for such a deceptive move, capitallize it, and the Juke emerges as Nissan’s newest vehicle. — capable of dashing through congested traffic with power, quickness and precision.

The Juke is deceptive in every way, defying traditional segments as easily as it slip through openings in congested traffic. It is not a car, really, nor is it a truck, and it’s not a sports car or crossover, either. Larry Dominique, who oversees Nissan project engineering, calls it “a sport-cross design that combines urban versatility with agile handling and adaptability.”

When it comes to unorthodox, Nissan is preparing to introduce its plug-in electric Leaf, and maybe the Juke is the perfect set-up for the Leaf. The Juke’s styling can generously be termed surprising, and the same goes for its power, which comes with a small 1.6-liter 4-cylinder, with direct injection and turbocharging to make its chain-driven, dual-overhead-camshafts run its dual variable-valve-timed 16 valves through their paces. Those paces run up to 188 horsepower at 5,600 RPMs, and 177 foot-pounds of torque, which hold that peak from 2,000-5,200 RPMs. Either a 6-speed stick shift of Nissan’s Xtronic CVT (continuously variable transmission) is available, as is either front- or all-wheel drive.

Estimated fuel economy is 27 city and 32 highway for the vehicle, which is built on a widened version of the subcompact Versa’s B-platform.Interior room is surprisingly spacious, with 10 cubic feet of storage behind the second row seat, or 35.9 cubic feet if you fold the rear seat down. The Juke measures 162.4 inches long, with a 99.6-inch wheelbase, and a width of 69.5, standing 61.8 inches tall.

Occupants sit up a bit higher than in most small cars, and Nissan is aiming the Juke at the Mazda3, Mini Cooper, Suzuki SX4, and Toyota Matrix and Scion tC. They might also have included the Honda Fit and the new Ford Fiesta hatchback. To take on such worthy competition, the Juke needs a low sticker price and a lot of performance agility, and Nissan made sure the Juke is well-endowed for either. Backing up its power, Juke base prices range from $19,710 to $25,300.

Without question, the Juke is startling when first seen. My first impression of the Juke front end’s wide-set headlights was a cartoon bullfrog. The lower fascia sweeps upward at both ends, and those headlights are plugged into the upper part of the fascia, right about where you might expect foglights to be. A thinner strip of lights runs vertically up and over the top edge of the fenders, and are visible from the interior. There is nothing weird about cartoons, or bullfrogs, by the way, and as many might find the Juke cute as unorthodox, but it is definitely far enough out of the mainstream to create its own channel.

Nissan has produced beautiful vehicles such as the 370 Z sports car, Altima and Maxima sedans, as well as the Infiniti G Coupe and Sedan, and the new M37 and M56 Infinitis. All are strikingly beautiful in design. Nissan also startled us all with the Murano crossover SUV, and the Infiniti FX models, which have been successful, even though their rounded-edge, rolling style falls more into the unusual region — something that must grow on customers. Same with the Rogue, Murano’s hot-selling and inexpensive compact crossover cousin.

Now comes the Juke, a new member to that ever-narrowing line between smaller crossovers and expanding subcompacts, literally crossing over to link both.The just-introduced Juke was voted to the candidate list for 2011 North American Car of the Year, but it might have been just as comfortable as a “mini-truck” of the year, if there was such a category.

Dominique will settle for the small crossover designation. “Small crossovers are expected to grow by 200 percent between 2005 and 2014,” he said, noting we are halfway from zero toward that 200 percent right now.

Typical with Nissan, the true beauty of the Juke comes from inside behind the steering wheel. A high shift lever, located on a circular mound of hard plastic, and other hard plastic surfaces on the dashboard, might lack the currently trendy soft-touch feel, but instruments are reminiscent of a motorcycle to the driver. Nissan says it is aiming the Juke at young males, which is not a surprise. In reality, young women — perhaps more secure in their identities — will readily buy macho-targeted vehicles, while young men might have nothing to do with a vehicle discerned as aimed at women.

Every gender will appreciate the Juke’s performance. Its turbo power zips around and through congested traffic, and it also is fun to drive on the highways. We got to try both. The Juke was introduced to the North American media at the Shangri La Hotel in Vancouver, and we were soon driving off through the city, then across the Lions Gate Bridge and up to catch the Horseshoe Bay Ferry to Langdale. From there, we drove north through some breathtaking scenery to our lunch destination at the West Coast Wilderness Lodge, before heading back toward Langdale and the ferry.

Nissan has been the most dedicated manufacturer to refine CVT automatics, which constantly shift via a belt while feeling as though they are never shifting, and that dedication is good reason the company is the most accomplished at the constantly-shifting system. Paddles allow the driver to squeeze the belt down to varying torque levels on the CVT, almost as effectively as a normal gearbox downshift. Power is distributed to either the front wheels or to all four, in all models.

Running through the base prices, before adding the $750 destination fee, the S model with front-wheel drive and VCVT is $18,960, and the AWD model is $20,460; moving up to the SV adds a moonroof and other features, costing $20,260 for the manual FWD, $20,760 for the FWD with CVT, and $22,600 for the AWD with the CVT; and the SL, which adds leather seats and navigation, starts at $22,550 for the FWD stick, $23,050 for the FWD with CVT, and $24,550 for the AWD with CVT.

At those prices, all Jukes come well equipped. The base model S has 4-wheel disc brakes, keyless entry, cruise control, 17-inch alloy wheels, 60-40 fold-flat rear seat, and speed-sensitive door locks and power-assisted steering, , and offers, and most of the features on the upgraded models, such as heated leather seats, navigation system with 5-inch screen, and iPod and Bluetooth connectivity, are available as options. And there is no “base” engine — all models come with the high-tech, turbo engine.

Volvo S60 looks hot, drives hot, still safe

NEWBERG, Oregon — Volvo’s long pursuit of safety has been well documented over the years, but less-known is Volvo’s long pursuit of being recognized among the finest European sports sedans. That fact became evident when Volvo introduced the long-awaited S60 to the North American automotive media in mid-September, before the cars reached U.S. showrooms.

Without question, the newest Volvo is the sleekest and sportiest Volvo sedan ever produced, with a strikingly sporty front end and grilled wrapping around its high-tech headlights, and a well-crafted roofline that meets the contemporary standards of being four-door coupe-like. Designed by Orjan Sterner, who was assigned to shape the raciest Volvo in the stable, it will be a big difference after the existing car’s 10-year run. The existing S60 has sold over 600,000, while the new one, built in Ghent, Belgium, is aiming at selling one-third in the U.S., one-third in Europe, and one-third in Asia.

We gathered in suburban Portland, where Volvo officials provided thorough background on the car and its capabilities before we went off on some hard-driving assignments that included hot laps around the road-racing course at Oregon Raceway Park, out near Mount Hood. Before we drove the car, Volvo officials said they anticipated selling it against everything from the Toyota Camry and Honda Accord on up, but its primary targets are the Acura TL, Audi A4, BMW 323 and 335X, the Infiniti G37X, and the Lexus IS-350.

After we had a chance to thoroughly wring out the new S60’s high-powered engine and flat-handling suspension during our day-long driving, the same Volvo officials admitted that its benchmark target was not the Audi A4, but the Audi S4 — the A4’s high-performance specialty car. None of us discounted that lofty ambition, after what we had experienced.

The new S60 has tremendous power, with a, familiar transverse-mounted in-line 6-cylinder engine measuring 3.0 liters of displacement, but internally reinforced and fitted with a twin-scroll turbocharger blowing fuel through 24 valves, activated by dual overhead camshafts. The result is Volvo’s most powerful 6-cylinder engine ever, with 300 horsepower at 5,500 RPMs and a whopping 325 foot-pounds of torque, peaking at 2,100 RPMs and holding that peak until 4,200 RPMs. The driver-adapted 6-speed Geartronic automatic transmission distributes that power to all four wheels.

A new S60 will cost $38,550, on up to $47,050 depending on choices. So intent is Volvo on gaining hot-sedan recognition that it was scarcely mentioned that after the S60 comes to the U.S. in full-out turbo-6 trim, a milder version will become available, equipped with Volvo’s very good inline 5, with or without turbocharging. That version should beat the test car’s 18-city/26-highway fuel economy numbers, even if it won’t match the turbo-6 for performance.

If the look is eye-catching, and the power is definitely Volvo-to-the-highest, the suspension of the car might be its most impressive single feature. Great attention was focused on eliminating the traditional Volvo leaning through sharp cornering. Volvos always have cornered very predictably, and nobody seemed to mind if the slightly stodgy and always-safe Volvos felt as though you might scrape the door handles on the sharpest turns. Nobody, that is, except those trying to compare with an S4, or a Mercedes AMG, or a BMW M3 — the targets Volvo assigned its engineers to catch.

MacPherson struts up front and multilink rear independent suspension both have asymmetricaly mounted coil springs, hydraulic shock absorbers and a stabilizer bar, and the struts have been thickened and the strut mounting stiffness incrased, as are subframe bushings, and the springs are shorter and stiffer. Along with a steering gear’s 10-percent improvement in quickness, the whole package is stiffened by 47 percent. Remarkably, the significantly firmer ride doesn’t ever approach harshness, while delivering vastly improved precision in tracing a curve without a hint of leaning.

The S60 comes with three chassis settings. The Dynamic chassis is standard, and is the same as in European delivery cars, which normally are firmer. The Touring chassis is a no-charge option and is a bit softer. The Four-C — for continuously controlled chassis concept — is an active arrangement with driver-selected choice of Comfort, Sport, or Advanced, and is optional. While the Touring would be the choice for softer coping with rough roads, the greatly stiffened parts of the Dynamic chassis would be the choice for those who like to corner hard. The Four-C, meanwhile, is a technical exercise, with sensors that continously monitor the car’s actions and adjust the dampers in fractions of a second to suit the situation. Engaging Sport mode meant the Geartronic would hold its gear changes longer.

Volvo’s experience with the Haldex all-wheel-drive system fits the latest Haldex perfectly with the steering, suspension and power improvements, and a cornering traction-control system alters the brakes on the inside wheels while adding power to the outside to help you get through a tight turn more effectively.

The race track duty proved the S60’s potential, although I didn’t have my usual enjoyment at Oregon Raceway. The 10-turn track was designed for optimum difficulty, and the designers went overboard to make nearly all the turns blind ones. You speed up a hill, and nothing but memorizing could tip you off to whether it was straight, left, or right on the other side of the crest. I was first in a line of six cars, which meant that all those behind could go hard as possible by keying on the car ahead, but I had nothing to key on, and I only went hard in spurts before letting off on the side of staying on the track. I had far more fun running hard on the curvy highways near Mount Hood on our way to the track.

The S60 is Volvo’s first new car since Ford Motor Company sold the Swedish company to a holding company that also owns Geely Automotive of China. The Chinese financing will help Volvo continue to build its unique cars, and, with a built-in partner, Volvo should rapidly expand its sales success in China. Ford and Volvo helped each other a lot during their relationship, and both seem headed for a prosperous future. For Volvo’s part, that means an unwavering attention to safety. The new S60 underlines that, offering all the proven Volvo concepts, such as lane-departure warning, driver alert control, distance alert, collision warning with full automatic braking, adaptive cruise control with brake assist, and a unique pedestrian detection with full auto brake.

We started our drive in the parking lot, aiming at a small, stuffed, child-size dummy positioned ahead. We were to get up to and hold 20 mph, continuing to steer right at the dummy, without touching the brake. It’s surprising how fast 20 feels as you head for what you’re certain is the inevitable splattering of the little doll, but suddenly — very suddenly, and very close to impact — the brakes are self-activated, hard and right to the point of lockup. And your S60 stops inches short of impact.

A coordinated system that has radar and a camera pointed ahead works seamlessly. The radar in the grille, used also for keeping the adaptive cruise-control space behind a car, detects any object ahead and its distance away; the camera, located on the front facing of the inside rear-view mirror, determines what that object might be. Unbelievable as it sounds, it can detect the swinging of arms or leg motion, comparing it to over 10,000 stored impressions of people, and if it determines that it is a person, the S60 tracks it until you have safely passed. If it steps out in your path as you approach at urban speed, the system will stop the car.

It might drive you crazy in a congested city, or driving through a college campus, where jaywalking seems to be a requisite, because you could find yourself stopping avery 20 feet or so. But Volvo is not joking about such devices. Thomas Broberg, director of Volvo’s amazing safety laboratory in Gothenberg, Sweden, said that in the U.S., 11 percent of all traffic fatalities are pedestrians. Broberg’s focus in recent years has been to keep trying to improve Volvo’s legendary safety, but to strive to find ways to make the driver safer, willing or not.

Volvo started 40 years ago to monitor and compile information from every fatal accident involving a Volvo in Sweden. “We have been able to reduce the risk of fatal crashes in Volvos by 60 percent,” Broberg said, explaining that Volvo also can detect when a driver might be getting sleepy or inattentive, and sound an alert by using the lane-departure technology that sounds if you drift over the dotted line without signaling. “As a driver gets tired, he might drift across the line more, but he also makes more micro-corrections on the steering wheel.”

Keeping the driver alert is a breakthrough in automotive engineering, as is the pedestrian-proof stopping system, which can also help stop the car at any speed when it’s detected to be closing too fast on any object at any speed. At the other end of the spectrum, as we approached the race track in western Oregon, I was second in a group of four S60s when I spotted a small sign that indicated we were supposed to make a 90-degree left turn. The lead car didn’t see it and went straight, as did the third and fourth cars. My reaction, at 60 mph, was sudden as I cranked the steering wheel, and we shot around that corner with incredible precision, and without any leaning.

Amazing that the new S60, which is aimed to take on the hottest-performing midsize cars, is also not about to compromise its intent on building the safest car in its class.

Tony’s ‘curse’ voids Indy 500’s final drama

It was altogether fitting and proper that Dario Franchitti won the 2010 Indianapolis 500. He drove the best race, had the fastest car all day, and might have won a dominant race had it not been for so many yellow caution slowdowns, which force a diminished-speed, single-file order. However, the race was still plagued by the dark cloud that Tony George has forcefully pulled over the legendary Indianapolis Motor Speedway, preventing it from ever attaining the magic it used to have, or the full drama it so richly deserves.

George was in charge back in the 1990s, when the Indy 500 was a fabulous event, the biggest single sports attraction in the world, every year. They would pack 400,000 people into the Speedway, with about 275,000 of them in seats all around the 2.5-mile oval, and the rest partying like crazy in the infield and every other standing-room area available. You had to reserve a room almost a year in advance, and pay a doubled or tripled rate with a three-day minimum, to secure a hotel spot. The whole event took literally an entire month of May to organize, promote, and hold two weekends of qualifying. The first day of qualifying, in fact, might have qualified as the second largest sports attraction in the country every year, because well over 100,000 would show up to watch drivers circle the track one at a time, for four lonely but high-pressure laps.

But because CART, the Championship Auto Racing Teams, had evolved into a far bigger and more popular season series than the old USAC series, CART drivers and teams would take a couple weeks off from their own schedule and come to Indianapolis to dominate the Indy 500. All of the CART races were bigger than all the USAC series except for Indy. So the CART teams wound up having the most clout when it came to rule changes. It didn’t matter how good CART was, the Indy 500 was the biggest race in the world.

When Indy 500 and CART racing were at their pinnacle, Tony decided he was tired of the bigshots from like Roger Penske and Chip Ganassi and a few others coming to the track and dominating the race against the host race teams. Although CART’s rules were more progressive, Tony George rebelled — basically against CART, but also, in a way, against his own institution. He declared new rules that would allow the previous year’s CART cars, but specifically outlawed the already-built new cars. He knew full well that CART teams had sold off their year-old race cars and already built new cars with their costly changes. Tony was right on about one thing — the cost of racing at that level was out of hand.

So Tony George declared his rules, which effectively eliminated the CART teams from participating. CART owners realized they were being locked out, and formed their own 500-mile race on the same weekend as the Indy 500, at Michigan International Speedway in Brooklyn, Mich. Tony whined that CART was boycotting Indy, and some of the lesser-informed media types bought it, so the split became a chasm.

Tony George trumpeted that his Indy Racing League would be for U.S. drivers, driving U.S. cars; for guys who grew up on the Sprint car and other dirt-track ovals. Sounded good, but high-speed racing had gone far beyond that charming, albeit neanderthal, notion. Racing at over 200 mph required the precise touch of drivers who had grown up learning how to race in high-speed go-karts and open-wheel formula cars, not the heavy-handed, rough-hewed guys who could horse a bounding dirt-track sprint car through a four-wheel drift on an oval.

One of those expensive CART rule changes was to reconfigure the cockpit, encircling it with a padded, horseshoe-shaped device around the sides and back of the cockpit. Designed in concert with doctors, the theory was to prevent a driver’s helmeted head from moving far enough in any direction to strike the side or rear of the cockpit in the case of a severe impact. Regardless of the impact, a driver’s head couldn’t snap more than about a half-inch to either side or the rear before it would come up against that cushioned collar. Typically, while the engines and the aerodynamics in the quest for speed got all the headlines, the high cost of making the dangerous sport of 230-mph auto racing as safe as possible.

Carrying out its end of the hassle, CART held its own race at Michigan International Speedway’s oval, on Indy 500 weekend. The 500 had the name and the fame and the history and the tradition, but the Michigan race had more advanced and wealthier teams, faster cars with higher technology, and better drivers. I went to MIS for what should have been a better and more significant race. Once there, I interviewed car-builders and doctors involved in the CART updates for a story I wrote for the Minneapolis Tribune, to disclose the underlying reasons for the cost increases that led to the difference between the two groups.

A botched start prevented CART’s “U.S. 500” from being a huge success. The narrower MIS track meant racers would start in two rows, rather than three. At the start, the two front-row cars got too close together, and neither wanted to give ground. They bumped tires, spun, and caused an enormous chain-reaction crash that wiped out one-third of the field — and all of the positive strokes.

That mess is all that’s remembered from that weekend, but a terrible tragedy before race weekend was the worst situation. Scott Brayton, a Michigan native and the top individual driver left at Indy, was fastest, and won the pole. In practicing for the race, Brayton’s car spun out in Turn 4, and as he fought for control, the car skidded into the outer wall. Brayton died. The official word was that he was killed when his head struck the concrete wall. I was at MIS, but I saw numerous video replays of the crash, which left me shaking my head, because the impact was not that severe, and the car was not that badly damaged. Then I saw one overhead view, which I never saw publicly shown again.

When his car skidded sideways, the overhead view showed Brayton’s helmet snapping severely to the right, about 6-8 inches, and whiplashed back. His helmet never struck the wall, negating first reports that he died of a skull fracture when his head hit the wall. Scott Brayton died of a broken neck because of the severe side-to-side whiplash. In effect, Brayton died because of Tony George’s command that cars racing at Indy would be forced to contain costs, which meant they didn’t consider the updated safety elements CART demanded on its new cars.

That’s a sad story, although very little was made of it. By race day, the media was back to stressing the Indy-CART split, and ridiculing CART for its first-lap crash.

For several years, CART continued to run U.S. 500s, moving to the oval at suburban St. Louis. They ran it on the Saturday when the Indy 500 was on Sunday, so I covered both. I drove to St. Louis, covered the CART 500, then drove late into Indianapolis, where I had a choice of several rooms from whatever motel I stopped at. Gone was the three-day minimum, gone were the inflated rates, and gone was the demand for tickets.

Years later, CART faded, and so did the IRL, but the Indy 500 remained. Some top CART team sponsors informed their teams that they didn’t care about the rest of the season, they only cared that the team race at the Indy 500. Roger Penske went back, playing by IRL rules. So did Chip Ganassi. Those two naturally went on to run the whole season of the newly renamed Indy Racing League, and wound up dominating.

Tony George boasted about having won the war. But what did he win? His basic premise was U.S. drivers from U.S. teams, with U.S. built cars and engines, but the top drivers were coming from Brazil, Europe, Sweden, Canada, and all over the globe. The cars were designed and built in England. The engines were Oldsmobile and Infiniti, and then Chevrolet and Toyota, before Honda, the mainstay in CART, came back to the series too.

Honda engines proved so dominant that Chevrolet and Toyota pulled out of the series. You may or may not have noticed that all 33 cars this year and for the past several years were powered by Honda engines. Nobody blows engines any more, that’s how good the Honda engine technology is. So we have 33 cars that are essentially the same Dallara chassis, running the same Honda engines. It is spec racing at its best — high-tech, but all identical cars and engines. Crowds are a little better, but have not found their way back to making Indy a must-see event.

If you watched the 2010 race, it came extremely close to being the exact sort of fantastic finish that might have caused race fans to rediscover the Indy 500. Franchitti zipped into the lead on the first lap, and he led all the way, yielding only for a few laps when he’d make pit stops, then quickly regain the lead as later-pitting cars came in. Tony Kanaan was a hero, starting 33rd and working his way all the way up to second, and appearing to be Franchitti’s top challenger, along with Helio Castroneves, Franchitti’s top rival. Both Kanaan and Castroneves, however, dropped back before the final laps, needing late pit stops to avoid running out of fuel.

It might have been a humdrum finish, but in the last 20 of 200 laps, a new threat suddenly emerged. Fuel became a problem for Franchitti, too, who was informed by his crew to cool it, to slow down from his 220-mph laps to more like 205 to conserve fuel. He did it, reluctantly, because he had a large lead, and because he knew that if he dashed to the pits for even a splash of fuel, he would blow the lead and the race to Dan Wheldon, who had worked his way up to second, and was closing in. Wheldon’s crew was giving him similar warnings — slow down, or you’ll run out of fuel, but Wheldon said he checked his instruments, and believed he was not in danger, and could have gone harder. He followed his crew’s demands, but he didn’t slow as much, and was still closing in. As the final laps melted away, Wheldon trailed by only the length of the straightaway, and then by less.

As the cars hurtled into their last three laps, the drama was nearing the boiling point. Would Franchitti’s pace be sufficient to hold off Wheldon? If he increased his pace, would he run out of fuel? Would Wheldon also speed up, and did he also face the risk of running out of fuel? Incredibly, Wheldon’s crew stuck by their orders. Had he been turned loose — why protect second place? — I believe he would have overtaken Franchitti, or at least closed in enough to force Franchitti to speed up and run out of fuel.

Coming around to start the last lap around the 2.5-mile oval, the drama was riveting. It was at that precise moment that what we shall call “The Curse of Tony George” struck. Everybody was charging as hard as they dared. Back in the pack, someone named Mike Conway was making up ground, and started to pass someone named Ryan Hunter-Ray, when Hunter-Ray’s car ran out of fuel. When his engine sputtered, Hunter-Ray abruptly slowed, right into the trajectory of the charging Conway. Their cars bumped wheels, and the impact sent Conway’s race car somersaulting over the top of Hunter-Ray’s car and into the outer wall and catch fence. The car did what it was designed to do, disintegrating to absorb impact. Doing that saved Conway’s life, perhaps, although it also scattered chunks of its carbon fiber bodywork all over the track.

Back up front, starting their final lap toward possibly the most dramatic finish in recent Indy history, the yellow caution flag waved and the caution lights flashed all around the oval. Franchitti, clinging to a tiny lead over Wheldon, slowed down immediately, because a caution means single file, with no passing. Conway was lifted out of the wreckage that had been his car, and airlifted to a hospital with a broken leg, but he never lost consciousness.

Franchitti stroked it around the last lap and crossed the finish line, with Wheldon second. Later, Franchitti’s crew said he had 1.6 gallons of fuel left, which was enough to get him around one last lap at reduced speed, but it would NOT have been enough for him to finish at the increased speed he would need to hold off Wheldon. But Wheldon was justifiably frustrated, because his crew found he had more than enough fuel to go hard, as his onboard instruments indicated, and either win the race outright or push Franchitti and win the race when Franchitti ran out of fuel.

Instead of the ultra-drama we viewers had been promised, we were left with the anticlimax of Franchitti cruising slowly to take the checker under yellow. A deserving winner, based on the whole day’s work, but in an outcome that left a few million television viewers drama-deprived and cheated out of a dramatic finish. Tony George has relinquished power at the 500 now, but his presence remains, as The Curse of Tony George.

Range Rover, LR4 sure-footed cliff-dwellers

TELLURIDE, Colo. — “All right, now,” said our Land Rover driving guide. “There’s a jogger coming toward us, so why don’t you stop right here.”

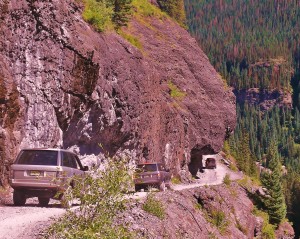

Not a bad idea, since we were just getting started on our unbelievable “Land Rover Colorado Experience 2010” drive, having left our palatial Lumiere Hotel rooms behind, driven into downtown Telluride, which is located at the bottom of a Rocky Mountain canyon, and then our caravan of Land Rover LR4s and Range Rovers turning 90 degrees left off the main street of town, to start driving up from 9,000 feet on something that was described as a county road, but was more a jagged rock-pile formed into a small ledge indenting the side of the San Juan Mountains.

We were divided up, two journalists with — thankfully — an expert off-road driving guide from Land Rover in each vehicle. When they spoke, we acted. So when our guy said stop, I stopped. The jogger — somebody local or else a crazed, high-altitude-overload training fanatic — came slowly along, with a dog on a leash. Stopping allowed the jogger to pass without facing a moving vehicle. It still was testy, because if you looked out our right side windows, you saw we were about 2 feet from a cliff with several hundred feet of sheer drop, and if you looked to the left you saw we had about 2 more feet to a rock wall that reached to the sky.

Our project was a two-day trek. We started in Telluride, which is a town that blossomed from 700 to 4,000 residents when the Rio Grande Southern railroad opened a run from Ridgway in 1870 to service the miners, and then dissolved to near ghost-town status in the 1950s, reviving only as a new and trendy ski-resort town in 1972. The cliffside roads up from Telluride were built to allow gold and silver miners to get to the mines that were dug at random in the mid-1800s. Those roads haven’t been maintained as actual roads since. Aside from the occasional off-road Jeeps and purpose-built specialty trucks and buggies, our caravan of shiny new Range Rovers and LR4s stood out, and as the vehicles soon became less-shiny, they also became much more appreciated by us, because our lives depended on them.

“We have an emotional attachment to this area,” said Finbar McFall, the colorful Irishman who is vice president of marketing for Land Rover/Range Rover. “When Land Rover first came to the U.S., they brought their vehicles to the Great Divide. It was appropriate then, and it’s more appropriate now. This is what our vehicles were made for; they may be made in England, but they were made for here. These are the lightest and most fuel-efficient vehicles we’ve ever made. They are also the most luxurious and most capable vehicles we’ve ever made. Luxurious and capable shouldn’t be compatible, but they are, in these vehicles.”

There were 13 automotive journalists attending the far-out unveiling of the 2011 LR4 and Range Rovers, and all of us knew that when Land Rover holds an introduction, it’s an adventure — whether taking on Utah’s Moab Desert, negotiating a special Land Rover course in Quebec’s Laurentian Mountains, or revisiting the Continental Divide country of highest-altitude Colorado.

These 2011 models are the best vehicles the British company has ever built, although in their 40-year history, they always have been over-engineered for normal use. My experience with them goes back to the 1990s, when they first came to the U.S., but before they became cult-figure vehicles for Hollywood movie celebrities. As soon as I examined and experienced the steel-girder-like frame rails and the lengthy suspension travel, as well as the armor-plating on the underside, I declared that Range Rovers would be the vehicle of choice if you were driving to Hudson Bay — without using roads.

Bob Burns, the headmaster of the group of dedicated off-road experts who work for the company, explained that the 14-day launch in 1990 along the Great Divide was being revisited because, in recent years, the fierce competition among SUVs was focused on-road. “While our vehicles stressed on-road, there never was a penalty for serious off-road use,” said Burns. “But we neglected our off-road capabilities, and a lot of people have gotten away from off-roading.”

Something like 95 percent of SUV buyers don’t ever take their vehicles off-road, but most of those who buy Range Rovers and Land Rovers do, and they are encouraged to take them to the most rugged and challenging sites around the world. Another side to the company’s healthy perspective on off-roading is its “tread lightly” focus on maintaining and keeping off-road areas unspoiled. Even a region as rugged and stunningly beautiful in its desolation as the San Juan Mountain range.

“Every time we go to an off-road area, we know that we have to take care of it, or it will go away,” said Burns. “There are environmental groups who want to close down off-road facilities, but we’ve proven we can leave them in better condition than we find them. We don’t want to damage any part of the environment, but at a place like this, we are driving on roads that haven’t been maintained for 120 years, so we aren’t damaging anything. A lot of people like to hike, but if you hike, you can see only a tiny percentage of what’s here. On this drive, you will see things that very few people in the world will ever see.”

Our route took us up the numerous switchbacks to scale one side of the canyon’s wall. We passed numerous abandoned mines to reach Imogene Pass, which is at 13,000 feet, and continued on the rugged road that was originally created to get through Ute Indian country. We came down into the town of Ouray, and checked into the Beaumont Hotel. We went from the ultramodern, year-and-a-half-old Lumiere Hotel in Telluride, to the Beaumont Hotel in Ouray that had long been abandoned until it was bought and totally restored in 2001. “It’s like a snapshot of the 1800s,” Burns said.

Ouray is a tiny town that was named after the chief of the Tabeguache Utes, who had once rebelled against Indian Agent Nathan Meeker’s attempts to herd them onto a reservation in 1880, as part of swindling them out of their land for the sake of those randomly probed gold and silver mines. All along our trek, the dozens of abandoned mines could easily be spotted by the residue of discolored rocks and gravel hanging like dried teardrops from those holes in the mountain range.

Consider that we drove, except for lunch stops, from 9 a.m. until 7 p.m.for two days, and while we were exhausted from the absolute focus required to pick our way over the smallest choice of boulders, we only covered a total of 80 miles, with no more than 15 of them on real roads. Our vehicles were fortresses designed for such duty.

The LR4 has a base price of $48,500, and in many ways is the more versatile family hauler, because it has three rows of seats to house seven occupants. An enormous sunroof covers virtually the whole top — open-air above the front seats and sunroof above the rear. The Range Rover steadfastly remains a two-row vehicle, uncompromising in its combination of interior luxury, with rich wood and leathers, and audio systems, and rugged, go-anywhere capability. Range Rovers are sometimes bought as status symbols by celebrities, but the company men prefer that those who buy them take them interspers serious off-roading along with the smooth highway cruising.

Range Rovers start at $60,495 for the Sport model, $79,685 for the HSE. Both the LR4 and the Range Rover use the 5.0-liter Jaguar V8, a direct-injected, dual-overhead-camshaft gem with variable valve-timing, turning out identical numbers of 375 horsepower at 6,500 RPMs, and 375 foot-pounds of torque at 3,500 RPMs. That power was more than enough, even for the extremes we confronted and conquered, but if you get the Range Rover, you can choose the supercharged version to boost power from 375 to 510 horses, and from 375 to 461 foot-pounds of torque, a peak that is spread out from 2,500-5,550 RPM, although that adds another $15,000 to those base prices. The LR4 is still the solid, body-on-frame construction with hydroformed, high-grade steel frame components and double-zinc-coated steel body panels, while the new Range Rover has been refined with a one-piece monococque body attached to three steel subframes, for the best of both worlds. The fenders, hood and doors of the Range Rover are aluminum for light weight, and the rest is double-zinc-coated steel.

We had driven an LR4 the first day, so we switched to a Range Rover the next morning, when again we had bright, sunny weather as we drove from Ouray to Silverton, our lunch destination. Later we climbed back up to the top of the world, preparing for a spectacular descent, on Black Bear Pass Road, where we crept down a series of switchbacks that even now, in memory, seem impossible to have attempted. With all that available power, it seems an incredible irony that the best part of both vehicles is their ability to inch down severe, treacherous cliffs.

In either the LR4 or the Range Rover, the console-mounted controls become vital. The ZF 6-speed automatic has command shift that sets to normal, sport or manual, and the permanent 4-wheel drive has 4-wheel electronic traction control, while the 2-speed-transfer allows shifting on the move with an infinite variable lock on the center differential.

Terrain Response is operated by a knob on the console, which can modify the engine, transmission, both differentials, the DSC, as well as the traction control, by which click of the knob you select.One setting is for general roadways, with alternatives for grass-gravel-snow, mud and ruts, sand, and finally to rock crawl. With all of that, you might shift the gear lever into “1,” locking the differential into low range 4×4. Terrain Response modifies the responsiveness of your engine, transmission, both front and rear differentials, the DSC (dynamic stability control) governing active roll mitigation, cornering brake control, and hill descent control. Thank God for hill descent control.

Amazingly, once engaged, you can take your foot off the gas and leave it poised but not riding the brake, and the system causes the big truck to tiptoe down the steepest grade, or pile of rocks and boulders, at something like 1 mile per hour. When we got to the top of Black Bear Pass Road and started our descent, I turned the main knob of Terrain Response to “rock crawl,” made sure we were in low-range lock, and shifted into first gear, as instructed.

Black Bear Pass Road descends from the still-standing hydroelectric station perched on the top of the cliff, next to Bridal Veil Falls, the highest waterfall in Colorado, and the road itself is described as “a treacherous series of one-way switchbacks.” Treacherous? My co-driver and I alternated driving and sitting in the right rear, so our guide could sit in the front passenger seat. Before we got to Black Bear Pass, I heard our guide tell my city-dwelling co-driver: “I want you to concentrate now on being gentle on the gas and hard on the brakes — because right now, you’re doing the opposite.”

My co-driver, however, fell victim to a high-altitude headache on the second day, and said he didn’t feel up to the concentration and would forfeit his turn at driving. That allowed me the combination thrill and relief of driving all the way down that cliff, back to Telluride. As a veteran of successfully scaling the icy avenues of Duluth, MN., in the winter, I was greatly relieved to drive that whole stretch, enjoying the adrenaline high. Extremely focused driving is the easy winner, compared to sitting helplessly in the back.

The cliff where we started our descent is a stark, granite facade, rising 2,400 feet above Telluride, and that thin column of water splashing down the wall nearby is Bridal Veil Falls, the highest waterfall in Colorado. Some of the switchbacks on the rugged and primitive trail are shaped more like a “Z” than an “S,” which means that even with quick steering and an excellent turning radius, there was simply no way to make the turns in one swing. Our guide got out, stood at the precipice, and waved me forward. “More…more…more…” he said.

“You’ve got to be kidding!” I responded, because there was only what remained of 2,400 feet of air visible beyond the hood of the Range Rover. “You’ve got to trust me,” he said. To which, I answered, “Yeah, but you’re out of the vehicle!”

I inched forward until he finally said “stop.” I stopped, and needed no reminder to hold my foot firmly on the brake pedal, then engage the emergency brake, then with my foot still on the brake, shift to reverse. That way, there was no creeping forward, which might have led to something more than “creeping” downward.

When we finally got to the bottom, the caravan stopped to change the right front tire of one of the other Range Rovers. My co-driver seemed miraculously recovered and asked to drive the rest of the way. That was through the town of Telluride and the luxuriously smooth ride on the short stretch of highway we enjoyed back to our Lumiere Hotel. Instantly, it seemed incomprehensible to consider what we had just done. that we had just driven . Never had we driven so long, with riveted focus on every inch of moving up, over, and down, for two full days, yet covering so few total miles.

Land Rover vice president of communications Stuart Schorr said: “Our customers can spend a day on these trails and see sights most people will never see.” We had done exactly that, witnessing sights and sensations that only precious few other humans — beyond the Utes and the miners — will ever see.

John Gilbert is a lifetime Minnesotan and career journalist, specializing in cars and sports during and since spending 30 years at the Minneapolis Tribune, now the Star Tribune. More recently, he has continued translating the high-tech world of autos and sharing his passionate insights as a freelance writer/photographer/broadcaster. A member of the prestigious North American Car and Truck of the Year jury since 1993. John can be heard Monday-Friday from 9-11am on 610 KDAL(www.kdal610.com) on the "John Gilbert Show," and writes a column in the Duluth Reader.

John Gilbert is a lifetime Minnesotan and career journalist, specializing in cars and sports during and since spending 30 years at the Minneapolis Tribune, now the Star Tribune. More recently, he has continued translating the high-tech world of autos and sharing his passionate insights as a freelance writer/photographer/broadcaster. A member of the prestigious North American Car and Truck of the Year jury since 1993. John can be heard Monday-Friday from 9-11am on 610 KDAL(www.kdal610.com) on the "John Gilbert Show," and writes a column in the Duluth Reader.