Tony’s ‘curse’ voids Indy 500’s final drama

It was altogether fitting and proper that Dario Franchitti won the 2010 Indianapolis 500. He drove the best race, had the fastest car all day, and might have won a dominant race had it not been for so many yellow caution slowdowns, which force a diminished-speed, single-file order. However, the race was still plagued by the dark cloud that Tony George has forcefully pulled over the legendary Indianapolis Motor Speedway, preventing it from ever attaining the magic it used to have, or the full drama it so richly deserves.

George was in charge back in the 1990s, when the Indy 500 was a fabulous event, the biggest single sports attraction in the world, every year. They would pack 400,000 people into the Speedway, with about 275,000 of them in seats all around the 2.5-mile oval, and the rest partying like crazy in the infield and every other standing-room area available. You had to reserve a room almost a year in advance, and pay a doubled or tripled rate with a three-day minimum, to secure a hotel spot. The whole event took literally an entire month of May to organize, promote, and hold two weekends of qualifying. The first day of qualifying, in fact, might have qualified as the second largest sports attraction in the country every year, because well over 100,000 would show up to watch drivers circle the track one at a time, for four lonely but high-pressure laps.

But because CART, the Championship Auto Racing Teams, had evolved into a far bigger and more popular season series than the old USAC series, CART drivers and teams would take a couple weeks off from their own schedule and come to Indianapolis to dominate the Indy 500. All of the CART races were bigger than all the USAC series except for Indy. So the CART teams wound up having the most clout when it came to rule changes. It didn’t matter how good CART was, the Indy 500 was the biggest race in the world.

When Indy 500 and CART racing were at their pinnacle, Tony decided he was tired of the bigshots from like Roger Penske and Chip Ganassi and a few others coming to the track and dominating the race against the host race teams. Although CART’s rules were more progressive, Tony George rebelled — basically against CART, but also, in a way, against his own institution. He declared new rules that would allow the previous year’s CART cars, but specifically outlawed the already-built new cars. He knew full well that CART teams had sold off their year-old race cars and already built new cars with their costly changes. Tony was right on about one thing — the cost of racing at that level was out of hand.

So Tony George declared his rules, which effectively eliminated the CART teams from participating. CART owners realized they were being locked out, and formed their own 500-mile race on the same weekend as the Indy 500, at Michigan International Speedway in Brooklyn, Mich. Tony whined that CART was boycotting Indy, and some of the lesser-informed media types bought it, so the split became a chasm.

Tony George trumpeted that his Indy Racing League would be for U.S. drivers, driving U.S. cars; for guys who grew up on the Sprint car and other dirt-track ovals. Sounded good, but high-speed racing had gone far beyond that charming, albeit neanderthal, notion. Racing at over 200 mph required the precise touch of drivers who had grown up learning how to race in high-speed go-karts and open-wheel formula cars, not the heavy-handed, rough-hewed guys who could horse a bounding dirt-track sprint car through a four-wheel drift on an oval.

One of those expensive CART rule changes was to reconfigure the cockpit, encircling it with a padded, horseshoe-shaped device around the sides and back of the cockpit. Designed in concert with doctors, the theory was to prevent a driver’s helmeted head from moving far enough in any direction to strike the side or rear of the cockpit in the case of a severe impact. Regardless of the impact, a driver’s head couldn’t snap more than about a half-inch to either side or the rear before it would come up against that cushioned collar. Typically, while the engines and the aerodynamics in the quest for speed got all the headlines, the high cost of making the dangerous sport of 230-mph auto racing as safe as possible.

Carrying out its end of the hassle, CART held its own race at Michigan International Speedway’s oval, on Indy 500 weekend. The 500 had the name and the fame and the history and the tradition, but the Michigan race had more advanced and wealthier teams, faster cars with higher technology, and better drivers. I went to MIS for what should have been a better and more significant race. Once there, I interviewed car-builders and doctors involved in the CART updates for a story I wrote for the Minneapolis Tribune, to disclose the underlying reasons for the cost increases that led to the difference between the two groups.

A botched start prevented CART’s “U.S. 500” from being a huge success. The narrower MIS track meant racers would start in two rows, rather than three. At the start, the two front-row cars got too close together, and neither wanted to give ground. They bumped tires, spun, and caused an enormous chain-reaction crash that wiped out one-third of the field — and all of the positive strokes.

That mess is all that’s remembered from that weekend, but a terrible tragedy before race weekend was the worst situation. Scott Brayton, a Michigan native and the top individual driver left at Indy, was fastest, and won the pole. In practicing for the race, Brayton’s car spun out in Turn 4, and as he fought for control, the car skidded into the outer wall. Brayton died. The official word was that he was killed when his head struck the concrete wall. I was at MIS, but I saw numerous video replays of the crash, which left me shaking my head, because the impact was not that severe, and the car was not that badly damaged. Then I saw one overhead view, which I never saw publicly shown again.

When his car skidded sideways, the overhead view showed Brayton’s helmet snapping severely to the right, about 6-8 inches, and whiplashed back. His helmet never struck the wall, negating first reports that he died of a skull fracture when his head hit the wall. Scott Brayton died of a broken neck because of the severe side-to-side whiplash. In effect, Brayton died because of Tony George’s command that cars racing at Indy would be forced to contain costs, which meant they didn’t consider the updated safety elements CART demanded on its new cars.

That’s a sad story, although very little was made of it. By race day, the media was back to stressing the Indy-CART split, and ridiculing CART for its first-lap crash.

For several years, CART continued to run U.S. 500s, moving to the oval at suburban St. Louis. They ran it on the Saturday when the Indy 500 was on Sunday, so I covered both. I drove to St. Louis, covered the CART 500, then drove late into Indianapolis, where I had a choice of several rooms from whatever motel I stopped at. Gone was the three-day minimum, gone were the inflated rates, and gone was the demand for tickets.

Years later, CART faded, and so did the IRL, but the Indy 500 remained. Some top CART team sponsors informed their teams that they didn’t care about the rest of the season, they only cared that the team race at the Indy 500. Roger Penske went back, playing by IRL rules. So did Chip Ganassi. Those two naturally went on to run the whole season of the newly renamed Indy Racing League, and wound up dominating.

Tony George boasted about having won the war. But what did he win? His basic premise was U.S. drivers from U.S. teams, with U.S. built cars and engines, but the top drivers were coming from Brazil, Europe, Sweden, Canada, and all over the globe. The cars were designed and built in England. The engines were Oldsmobile and Infiniti, and then Chevrolet and Toyota, before Honda, the mainstay in CART, came back to the series too.

Honda engines proved so dominant that Chevrolet and Toyota pulled out of the series. You may or may not have noticed that all 33 cars this year and for the past several years were powered by Honda engines. Nobody blows engines any more, that’s how good the Honda engine technology is. So we have 33 cars that are essentially the same Dallara chassis, running the same Honda engines. It is spec racing at its best — high-tech, but all identical cars and engines. Crowds are a little better, but have not found their way back to making Indy a must-see event.

If you watched the 2010 race, it came extremely close to being the exact sort of fantastic finish that might have caused race fans to rediscover the Indy 500. Franchitti zipped into the lead on the first lap, and he led all the way, yielding only for a few laps when he’d make pit stops, then quickly regain the lead as later-pitting cars came in. Tony Kanaan was a hero, starting 33rd and working his way all the way up to second, and appearing to be Franchitti’s top challenger, along with Helio Castroneves, Franchitti’s top rival. Both Kanaan and Castroneves, however, dropped back before the final laps, needing late pit stops to avoid running out of fuel.

It might have been a humdrum finish, but in the last 20 of 200 laps, a new threat suddenly emerged. Fuel became a problem for Franchitti, too, who was informed by his crew to cool it, to slow down from his 220-mph laps to more like 205 to conserve fuel. He did it, reluctantly, because he had a large lead, and because he knew that if he dashed to the pits for even a splash of fuel, he would blow the lead and the race to Dan Wheldon, who had worked his way up to second, and was closing in. Wheldon’s crew was giving him similar warnings — slow down, or you’ll run out of fuel, but Wheldon said he checked his instruments, and believed he was not in danger, and could have gone harder. He followed his crew’s demands, but he didn’t slow as much, and was still closing in. As the final laps melted away, Wheldon trailed by only the length of the straightaway, and then by less.

As the cars hurtled into their last three laps, the drama was nearing the boiling point. Would Franchitti’s pace be sufficient to hold off Wheldon? If he increased his pace, would he run out of fuel? Would Wheldon also speed up, and did he also face the risk of running out of fuel? Incredibly, Wheldon’s crew stuck by their orders. Had he been turned loose — why protect second place? — I believe he would have overtaken Franchitti, or at least closed in enough to force Franchitti to speed up and run out of fuel.

Coming around to start the last lap around the 2.5-mile oval, the drama was riveting. It was at that precise moment that what we shall call “The Curse of Tony George” struck. Everybody was charging as hard as they dared. Back in the pack, someone named Mike Conway was making up ground, and started to pass someone named Ryan Hunter-Ray, when Hunter-Ray’s car ran out of fuel. When his engine sputtered, Hunter-Ray abruptly slowed, right into the trajectory of the charging Conway. Their cars bumped wheels, and the impact sent Conway’s race car somersaulting over the top of Hunter-Ray’s car and into the outer wall and catch fence. The car did what it was designed to do, disintegrating to absorb impact. Doing that saved Conway’s life, perhaps, although it also scattered chunks of its carbon fiber bodywork all over the track.

Back up front, starting their final lap toward possibly the most dramatic finish in recent Indy history, the yellow caution flag waved and the caution lights flashed all around the oval. Franchitti, clinging to a tiny lead over Wheldon, slowed down immediately, because a caution means single file, with no passing. Conway was lifted out of the wreckage that had been his car, and airlifted to a hospital with a broken leg, but he never lost consciousness.

Franchitti stroked it around the last lap and crossed the finish line, with Wheldon second. Later, Franchitti’s crew said he had 1.6 gallons of fuel left, which was enough to get him around one last lap at reduced speed, but it would NOT have been enough for him to finish at the increased speed he would need to hold off Wheldon. But Wheldon was justifiably frustrated, because his crew found he had more than enough fuel to go hard, as his onboard instruments indicated, and either win the race outright or push Franchitti and win the race when Franchitti ran out of fuel.

Instead of the ultra-drama we viewers had been promised, we were left with the anticlimax of Franchitti cruising slowly to take the checker under yellow. A deserving winner, based on the whole day’s work, but in an outcome that left a few million television viewers drama-deprived and cheated out of a dramatic finish. Tony George has relinquished power at the 500 now, but his presence remains, as The Curse of Tony George.

Kenyans claim 9 of top 10 at Grandma’s

The question “Which Kenyan will win this year?” was far more than just cynical rhetoric in 2010, at the 34th running of Grandma’s Marathon, which had its familiar upbeat theme tinged with sadness in the aftermath. Kenya’s involvement was only joyful, with Philemon Kemboi leading a contingent that finished 1-5 and had nine of the top 10.

Kemboi’s surprising late bid left Chris Kipyego and David Rutoh behind over the final mile, and his third-to-first burst broke the Canal Park tape at 2 hours, 15 minutes, 44 seconds. It was Kemboi’s first marathon victory ever, although it was Kenya’s 10th in the last 14 Grandma’s Marathons.

The race will, unfortunately, be remembered for having sustained the first fatality in the Marathon’s 34-year history. Norman Ruth, 64, from Duluth’s suburb of Hermantown, finished the 20th Annual Garry Bjorklund Half Marathon, which started earlier in the day, but after finishing he required medical attention, and died of an apparent heart attack. He was attended at the medical tent near the finish line and then hospitalized, but didn’t recover.

While Duluth’s premier sports event is annually well-promoted and attains numerous pages of publicity, organizers were obviously unprepared to deal with the tragedy. Later on race day, only the fact that someone had died in the half-marathon was disclosed.

Meanwhile, out on the course along Lake Superior’s North Shore, the full marathon was being taken over by the three top runners, all making their first visits to Duluth. They led the swift crop of runners who make their annual pilgrimage to Duluth and return home by bolstering their East African nation’s economy.

“It was the biggest race I’ve ever won,” said Kemboi, who earned $10,900. “I will go home…and I will go to the bank. I feel good about being able to help my family’s life to improve.”

Kenya’s elite runners had won nine of 13 before Minnesota native Christopher Raabe won last year. Raabe ran among the leaders this year, too, and finished sixth as the only interruption to Kenya’s top nine places.

Things were much simpler to follow in the women’s segment, where Buzunesh Deba from Ethiopia, simply sped away from the start, and recorded a personal best 2:31:36 time to beat runner-up and fellow-Ethiopian Yeshimebet Bifa by almost four full minutes.

Deba moved from Ethiopia to New York four years ago, and said watching the New York Marathon in 2008 caused her to decide to become a distance runner. After competing in shorter 5K and 10K races, she started in marathons only last fall.

“The first marathon I entered I won,” she said. Her winning time in the California International Marathon was 2:32:17, and after running seventh in the New York Marathon, she sped into 2010 by winning the National Marathon to Fight Breast Cancer in Florida with a time of 2:33:08. So Saturday’s run was her best by almost a minute.

“My plan was to start fast and try to get ahead,” she said, laughing herself at such obvious strategy, except that she made work. She was alone by the 5-mile mark, and nobody else ever got within view of her.

Mary Akor, who had won the last three Grandma’s, finished fourth, behind the top two Ethiopians, and Everlyne Lagat. Akor, 33, has suffered with recent illness that is scheduled for surgery in the near future, and she had to yield to the youthful Deba, who is 22, and Bifa, 21.

The 20th annual Garry Bjorklund Half Marathon was also owned by African runners. Stephen Muange of Kenya won a close men’s segment in 1:04:24, three seconds ahead of Bado Worku, an Ethiopian who was closely followed by countrymen Derese Deniboba Rashaw and Worku Beyl. The women’s category was won by Caroline Rotich, in 1:12:40, nearly two minutes ahead of Alemtsehay Misganaw in a 1-2 Ethiopian finish.

The festive attitude of marathon day was as high-spirited as usual, because nobody had been informed that, hours earlier, Ruth had become the first fatality in the Marathon’s 34-year history. Dr. Ben Nelson, serving his first race as medical director, made the early evening announcement of the fatality, but said he met with race officials and they decided to release no other information.

The fatality was a shocking irony on a race day with temperatures in the mid-60s, about 20 degrees cooler than the year before, which greatly reduced the number of runners affected by the heat and high humidity. Dr. Nelson said in the full and half marathons, 230 runners required some medical attention, but only four from the finish-line tent and three others from out on the course were sent to hospitals for treatment — a significant reduction from recent years.

Withholding news of the tragedy, intentionally or not, left the day to the usual celebration, and the drama for the full marathon built throughout. Race-watchers along the North Shore saw the Kenyans dominate from start to finish, with the three front-running Kenyans pulling away around the 23-mile mark. By the time they glided off London Road and onto Superior Street, the three lead runners were alone. But even then, there was a surprise finish.

Kemboi, 36, whose best previous marathon time of 2:10:58 was good for only a fifth-place finish in France last year, was loping along right behind the tandem of Kipyego, 36, and Rutch, 24, who said they were anticipating which of the two would make the pivotal move for the lead. Kemboi burst past them both as they turned off Superior Street, and his more experienced rivals couldn’t match his finishing speed.

Kemboi is taller than most other Kenyan runners, at 5-foot-8 and 120 pounds, and when he stretched his legs out running down Fifth Avenue West, his winning time of 2:15:44 beat Kipyego by 16 seconds, with Rutoh three more seconds back in third. Kenyans Kipyegon Kirui and Kennedy Kemei were fourth and fifth. Sixth was Raabe, the Minnesota native who was a surprise winner last year. Raabe, who now lives in Washington, D.C., was followed by four more Kenyans, as the prolific elite visitors were the class of the 5,620 entries who finished the full marathon.

Despite the cooler conditions, the full marathon didn’t threaten any records. Kemboi’s winning time was far off the record established by Minnesotan Dick Beardsley in 1982, at 2:09:37 in the fifth year of the event. In fact, Kemboi’s 2:15:44 was a half-minute off last year’s winning pace, when Raabe won at 2:15:13. But the victory was a breakthrough for Kemboi.

A late starter in competitive running, Kemboi had grown up on a family farm near Kapsabet, about seven hours drive from Nairobi. His family never had a car, he said, and when he realized he could help his family by earning money in distance running, he started seriously training in 2004. Calf injuries hindered him for a couple of years, so he had only entered three previous marathons.

Inexperienced or not, he said, “I thought I could win it.” His top rivals were less convinced. Kemboi, speaking only his native Swahili via an interpreter, said he went along with Kipyego and Rutoh, his two countrymen, when they moved away from the pack. “It wasn’t a bad pace,” Kemboi said. “But when they decided to push forward, I was in agreement that we needed to pick up the pace.”

He said he thought he surprised them when he went for the lead as the three turned off Superior Street, down the Fifth Avenue West hill toward the harbor. Kipyego had run against Rutoh before, but didn’t know Kemboi. After the three leaders got away from the field, Kipyego was running alongside Rutoh and said, “I told this guy, ‘Let’s push, let’s push.’ I told him it was time to break away. I was expecting him, if anyone, to be the one to go for the lead.

“I didn’t know who this other guy was. When he went by us, I tried hard to close the gap, but he was very strong for me. I started thinking, ‘Is HE going to win the race?’ ”

He was, indeed.

Kipyego said Grandma’s is unlike other major marathons, which he suspects limit the number of Kenya runners invited. There were 27 at Grandma’s.

“I saw the list, with so many Kenyans, and I thought, ‘This will be fun,’ ” said Kipyego, He said his sister, Sally, became a top NCAA runner at Texas Tech after growing up running to keep up with her big brother. In Kenya, running ability is naturally attained by a different lifestyle from childhood. In the U.S., kids might be driven six blocks to a playground, a fact Kipyego found amusing.

“We had no cars, no buses, and there were no roads,” said Kipyego, who is from the city of Eldoret. “School was five kilometers away, and there was no school bus. We’d run to school in the morning, run home for lunch, then run back to school, and then run home, every day.”

That is a common thread among the Kenyan runners. Kemboi said he, too, ran from the family farm to school, but it was only one kilometer. Hardly proper training for an elite marathon runner. But even if 36 makes him a late-bloomer, his victory can be a springboard to more marathon invitations.

Perennial star Mullen leads perennial power Hawks

Pressure? What pressure? If there is anything resembling pressure on Hermantown’s return to Caswell Park in North Mankato this week to defend its Class AA Minnesota state high school softball championship, it was not noticeable — and with good reason.

The Section 7AA tournament provided as much pressure as Hermantown(23-4) was prepared to face Pipestone Area (20-1) in the opening state tournament game. It turned out that Hermantown beat Pipestone, and won a semifinal game as well, but lost in the championship game to fall one short of repeating as state champs.

But getting there was enough of a chore to remain in the Hermantown players’ memory banks forever. After the Hawks won their third straight Section 7AA title, coach Tom Bang acknowledged that he had an unfair advantage after the Hawks survived four consecutive elimination games to win the Section 7AA championship at Braun Park in Cloquet.

“Any time you have No. 4 going on the mound for you, you know you’ve got a real good chance,” said Bang.

No. 4 is Megan Mullen, whose pitching and hitting decided last Thursday’s pair of must-win victories over Duluth Central, who gave the most credit back to Bang. Mullen and fellow-senior Julia Gilbert have been standouts for four straight years, while Ellen Folman, another senior, has been a regular for three seasons.

That was no guarantee of anything, of course. In the sectional, the Hawks lost a 3-2 opening game to an aroused Duluth Central team, which was playing its final season as a separate entity before a controversial merging with Denfeld takes hold and the “red and white” falls victim to the “Red Plan.”

After upsetting Hermantown to open play on Tuesday of last week, Central also beat Denfeld to stand undefeated, while Hermantown had to beat Greenway of Coleraine right after the loss to Central, then had to also beat Denfeld in another battle the same day, where the loser was finished for the season.

That sent Hermantown back to the Thursday finals against Central, and the determined Hawks — knowing they had to beat Central twice to capture the title — blew out the Trojans 8-0 to set up an immediate rematch. With both teams having one loss, one more loss would mean the end of the season for Hermantown, and the end of the season and the program for Central.

Mullen and Central freshman Sarah Hendrickson duelled through three scoreless innings, then Mullen drove in the first two runs in the fourth, and another in the fifth, and pitched the Hawks to a 3-1 victory.

“Over the years, we’ve had a lot of outstanding players, including Lindsay Erickson, who went on to play for the Gophers,” said Bang, who is completing his 31st season as the architect of the dominant program. “But I’d have to say Megan Mullen is the most talented pitcher I’ve had, and probably the best player. We had four seniors last year, and 14 returned from the tournament roseter for this year.”

And it was Bang, Mullen said, whose strategic maneuvers helped turn Tuesday’s 3-2 loss into Thursday’s 8-0, 3-1 sweep, with the two setbacks ending Central’s outstanding season at 17-7. Central’s players played hard through both games, and showed great spirit, with their emotions finally running over during their final post-game huddle. The intensity of the two games meant both teams spent everything on the field, and in the end, Mullen’s hitting was a pivotal difference.

“My hitting?” said Mullen. “Tuesday didn’t go so good, but today worked out better. We set goals at the start of the season, and one of my goals was to bat over .400. I don’t know for sure what my average is now, but it’s somewhere around .420. But the biggest difference between us losing 3-2 to Central, and beating them twice is Mr. Bang. When they beat us, Central definitely had their bats going real well, but in these two games, Mr. Bang called the pitches. He had watched all their hitters, and that made a big difference. Central’s hitters are really good, and they recognize change-ups and adjust to hit them. So today we went with more hard stuff — I would say 98 percent of my pitches.”

Bang said his signal calling required no special genius, and he continued to go with her fast ball and other power pitches. “Her rise ball is hard, her curve is hard, and she has a little screwball that goes outside-in to right-handed hitters,” said Bang. “I like to get ahead in the count, so I like her fastball down and in or down and out. During the season, we beat Central 1-0 on a passed ball that only got about 6 feet away from their catcher, but Julia Gilbert beat the play home. Megan struck out 18 of 21 outs in that one.”

Mullen’s windmill pitching — which will be on display next season as a freshman at UMD — deserved high praise. She allowed four hits, walked one and struck out nine in the 8-0 game, when Bang took her ouot after five innings. With both teams mobilized for an all-out effort in the decisive second game, Mullen went all seven innings, allowed five hits, no walks, and struck out nine again. She sailed through six innings, giving up three hits, walking none and striking out nine, and just when it appeared she would hurl back-to-back shutout gems, Molly Jadzewski led off the seventh by blasting a home run over the right-centerfield fence, and Kylie Murray added a single before Mullen got out of further trouble.

But Mullen’s hitting was just as pivotal. Hermantown established itself with a 5-run top of the first inning. Mullen’s double drove in the first run, and Ellen Folman singled home two more. It got better in the second game, after Central regrouped to make its final bid, and Hendrickson battled Mullen evenly until the last of the fourth.

It was 0-0 when Julia Gilbert beat out a bunt single leading off the fourth and stole second. Rudi Summers bunted her to third and beat it out for another hit, then she also stole second, putting runners at second and third with none out. Mullen came up next and drilled a single to right, driving in both Gilbert and Summers for a 2-0 lead. That might have been the biggest hit of the season for Hermantown, but in case more was needed, Mullen singled home another run in the fifth to make it 3-0.

Going 2-3 and driving in all three runs was enough to deserve the spotlight, if it wasn’t for Mullen’s strong pitching. At the state tournament, of course, everybody has a story of similar heroics, and even though Mullen threw yet another no-hitter in the semifinals, the Hawks fell just short.

CENTRAL’S FINAL BID

On the other side of the Section 7AA final, Central coach Nat Brown knew what his Trojans were up against in the quest to finish off Hermantown.

“We knew going in that even though we were undefeated, we were going to have a tough time,” said Brown. “In our two earlier games against Hermantown [the 1-0 loss and Tuesday’s 3-2 victory], Julia Gilbert had scored all three runs against us, so how important was it to keep her off the bases? But we came out tight, she’s the first hitter up, we boot it, and they go on to score five.

“That made it tough. You don’t want to raise a white flag, but you almost wish you could just call the game and get ready for the second game.”

Brown pulled Sarah Hendrickson, who emerged as a standout pitcher despite being only a ninth-grader, after three innings, to help her get replenished for the rematch. She responded with a strong 5-hitter in the second game, striking out five.

“Sarah felt so bad between games,” said Brown. “She came up to me and said, ‘Sorry I let you down.’ I told her, ‘You’ve never let me down for a second.’ ”

Having finished his 10th year coaching, Brown now must re-apply to see if he will be allowed to continue coaching the newly combined Central-Denfeld team next year.

BANG’S EVENTFUL YEAR

Hermantown coach Tom Bang has had what you might call an eventful year since last year since the school year ended. On June 9, the Hawks won the state title — the school’s third. On June 10, he went in for heart surgery. He retired as a teacher, but he said he would stay on as softball coach. Now they’ve earned their way back to the state tournament for the chance to defend their state title, which begins one day after the anniversary of last year’s championship.

“I had a problem with my bicuspid heart valve, and developed an anorism in my aorta,” Bang said. “They replaced it with a metal valve on June 10. I knew the previous November that I would have to have the surgery, and one doctor said I should hve it within six months, so I knew I could make it until the season was over.”

By a day. With his heart situation in mind, was that why his players didn’t try to give him a Gatorade dowsing after winning the 7AA title? “No,” said Bang. “They got me last year, and I faked a heart attack.”

Bang, a lifetime resident of Hermantown, played baseball and football at the school before graduating in 1969.

“I started teaching in 1978, so I don’t know if that means I’ve coached 31 or 32 years,” said Bang.

Jill, his wife, knows full well that this is his 31st year coaching. It turns out that June 9 not only was the day the Hawks won last year’s state title, it was the 31st anniversary of Tom and Jill’s wedding. Three children, three state titles, and two state runner-up finishes later, Jill still remembers. “He didn’t really tell me about the coaching,” said Jill. “But if they’d won one more game that year, he would have missed our wedding rehearsal.”

This is the 17th time Bang has taken Hermantown to the state tournament in his 31 seasons. It also is the Hawks’ ninth straight Class AA tournament, although Hermantown took a break when it was boosted up to Class AAA for two years. That means Hermantown went to state in 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, and 2005, then moved up and failed to make the state AAA tournament in 2006 and 2007, and since returning to Class AA, the Hawks have won three straight sectionals.

Obviously, he hasn’t lost his passion for coaching, or his skill at maneuvering his carefully cultivated talent for success. And he’s learned to be a little flexible, too. They ran into daylong rain on Tuesday, but they held a pre-state tournament practice Monday. How did it go?

“It wasn’t bad, considering,” said Bang. “School’s out now, and the seniors had their all-night graduation party, so not everybody was as sharp as they could be.”

They were razor sharp for the state tournament, and fell just shy of their ultimate goal after a brilliant effort.

Badgers rise to playoff peak in time for Frozen Four

In the moments after Wisconsin won a tough and challenging West Regional championship, Badgers coach Mike Eaves could pause and wonder what happened to sidetrack Denver and North Dakota on their way to their appointed spots at the Frozen Four.

In the moments after Wisconsin won a tough and challenging West Regional championship, Badgers coach Mike Eaves could pause and wonder what happened to sidetrack Denver and North Dakota on their way to their appointed spots at the Frozen Four.

While he may have been puzzled that WCHA regular-season champion Denver and WCHA playoff champion North Dakota had both lost in other regionals, Eaves is a master pragmatist, capable of focusing on things that might be within his control. At that moment, satisfaction at having beaten Vermont, then reversing a league playoff loss to St. Cloud State was foremost. It earned the West Regional’s berth in the April 8-10 Frozen Four in Detroit, which now becomes something that might fall into that controllable category.

No. 2 ranked Wisconsin (27-10-4) faces RIT (28-11-1) in the 4 p.m. (CDT) first semifinal, with No. 1 Miami of Ohio (29-7-7) taking on Boston College (27-10-3) in the 7:30 p.m. second semifinal, with both games on ESPN2. The winners play at 6 p.m. Saturday, on ESPN.

“We’re blessed to have some awfully talented young men on this team, with a tremendous work ethic,” said Eaves. “They are selfless, capable of focusing on the team, and all things have come together for us at the right time. Last year, we were .02 points away from making the [NCAA] playoffs. That has been on our kids minds; we even had t-shirts made up.”

The Badgers, who finished second to Denver in league play, had to lift themselves up after reaching the Final Five, where they were blanked 2-0 by St. Cloud State in the semifinals. They rebounded the next day to beat Denver. As the No. 1 seed at the West Regional, Wisconsin beat Vermont before coming back with force to avenge that setback to St. Cloud State in the West Regional final.

“There was a lot of redemption for us [against St. Cloud State],” said junior defenseman Ryan McDonagh. “We didn’t play well last weekend [in the Final Five], and we knew what was riding on the game this time — going to the Frozen Four.”

Now Wisconsin faces the peculiar venue of playing the Frozen Four at Ford Field in Detroit — the Lions NFL stadium, which could produce record hockey tournament crowds. In that regard, the Badgers have the experience of having played in a football stadium already this season, having played and beaten Michigan 3-2 at Camp Randall Stadium, before 55,031 — a number that might be difficult to top in Detroit, with both Michigan and Michigan State conspicuous by their absence.

Boston College also played at Fenway Park on January 8, losing 3-2 to Boston University before 38,472 fans. Big-stadium experience notwithstanding, Wisconsin will make a formidible entry in the Frozen Four, with an overpowering defense, and a surprisingly unheralded scoring attack. The large, hard-hitting, and mobile defense, with five first- or second-round NHL draftees and a sixth who is certain to be drafted this year, are Wisconsin’s most evident asset.

An NHL expansion team would thrive with a defense that included juniors Ryan McDonagh, taken in the first round by Montreal in 2007; Brendan Smith, taken on the same first round by Detroit; and Cody Goloubel, taken on the second round in 2008 by Columbus; plus sophomore Jake Gardiner, a 2008 first-rounder by Anaheim; and freshman Justin Schultz, a 2008 second-round pick of Anaheim. That leaves only John Ramage, who started the season as an 18-year-old freshman from St. Louis. He’s the son of Rob Ramage, a 16-year NHL defenseman who was a first-round pick of Colorado in the 1979 expansion draft.

But don’t underestimate the forwards. Most notable up front has been captain and first-line center Blake Geoffrion, the lanky, 6-foot-2 grandson of Bernie (Boom-Boom) Geoffrion. With his hometown listed as Brentwood, Tenn., Geoffrion is undoubtedly going to be the first home-state performer for the Nashville Predators, who drafted Geoffrion on the second round. A key to the Badger season was when Geoffrion turned down th eoffer and decided to play his senior season at Wisconsin.

“We don’t have the team we have without Blake coming back,” said Eaves, matter-of-factly.

Geoffrion led the WCHA in conference scoring until the final day, when Denver’s Rhett Rakhshani slipped ahead — 15-20–35 to 19-15–34. But a funny thing happened to the team scoring lead in the playoffs. Geoffrion had a goal and an assist in the 3-2 West Regional victory over Vermont, and added a goal and two assists in the 5-3 victory over St. Cloud State, his overall total of 27-21–48 is impressive, and helped him win West Regional most valuable player status — but his points rank only third-best on the Badger team.

Senior Michael Davies has 19-32–51, and sophomore Derek Stepan has 10-40–50 to rank 1-2 on the Wisconsin team in all games. Junior defenseman Brendan Smith has 15-32–47 to rank one point behind Geoffrion’s total. Geoffrion is best with 14 power-play goals, while Stepan leads all league scorers with his 40 assists, while Davies and Smith — the league’s top-scoring defenseman — are tied for second best with 32.

“Our seniors have worked ever since our freshman year,” said Geoffrion. “It’s an incredible feeling to get to the Frozen Four.”

Then he pointed to “Mitchie” — John Mitchell, a 6-foot-5 crusher who scored twice in the region final. He had only five goals all season until adding those two. Mitchell, in turn, gave credit to the penalty-killers for stopping all seven Huskies power plays, and it’s understandable, because that’s a group he not only appreciates, but also personally gives them a lot of action.

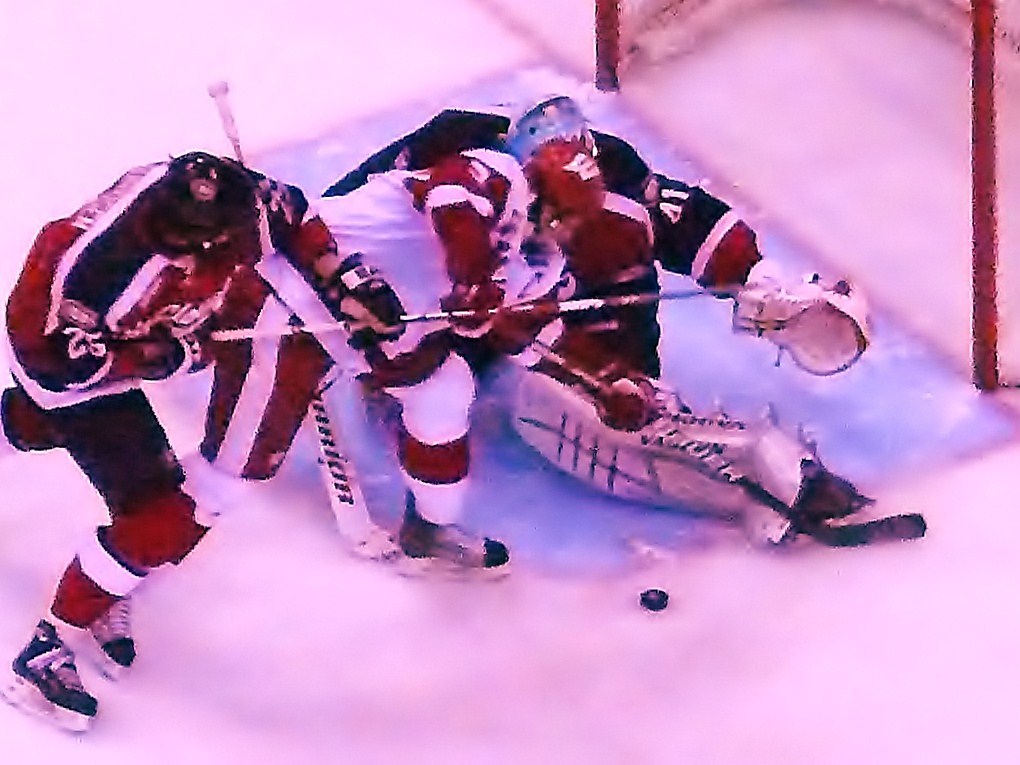

{IMG2}

“Our PK did a tremendous job,” said Mitchell. “I got five penalties in the two games [of the West Regional], and I think I’m going to have to limit those penalties.”

As for contributions from players like Mitchell — a free-agent senior who might also earn a lot of attention from NHL scouts after the season — Eaves, who has had numerous teams that had difficulty scoring and had to rely on defense and goaltending to survive.

“At this point, we’re looking for offense from anybody,” Eaves said. “And Mitch was very effective for us this weekend.”

As a further example of how this team has developed and matured, Eaves singled out another senior, and said: “Look at Aaron Bendickson. He had a great chance with an open net, but he bounced it off the post. He came back after that and played like he was possessed, and he wound up getting a goal. I’m not sure he would have reacted the same way at the start of the season, but that’s how focused we are now.”

The added burden carried by the Badgers into the Frozen Four will be shrugged off with two Wisconsin victories. But the league’s opportunity to get three teams to the Frozen Four seemed like the most lucrative since 2005, when Denver, North Dakota, Minnesota and Colorado College filled all four slots at the Frozen Four in Cincinnati, with Denver winning. Such success leads to questions about parity. Did the fact that WCHA champion Denver was upset 2-1 by Rochester Institute of Technology, and that WCHA playoff champion North Dakota had been upset 3-2 by Yale, mean that the proud Western Collegiate Hockey Association might not be as strong as we in the west would like to believe?

After all, while no other league can approach the 36 NCAA championships won by teams from the WCHA. And close followers of the annual league race and the spectacle of the WCHA’s playoff structure, resulting in the flashy Final Five tournament at Xcel Energy Center in St. Paul, can look with pride at the listing of years WCHA teams won those titles. It does appear, however, that someone hasn’t been keeping that list up to date, because after it shows “…1997, 2000, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006…” there aren’t any more years listed. What happened to 2007, 2008, and 2009?

Correct. The proud WCHA, which won so regularly that in 2005 Denver, North Dakota, Colorado College and Minnesota made it an all-WCHA Frozen Four, and which won five consecutive NCAA titles up through 2006, hasn’t won since.

That, of course, isn’t a problem for the Badgers. They won that 2006 title, and while they might prefer to see some familiar WCHA faces across the rink, their only challenge is to be ready to win two games and recapture the title for the WCHA.

WCHA bids 4 aces into NCAA puck tournament

Can North Dakota maintain its hot streak? Can Denver recover from losing two straight for the first time all season? Can Wisconsin channel its consistency into sudden-death mode? And can St. Cloud State turn its back on its curious 0-forever NCAA record?

Can North Dakota maintain its hot streak? Can Denver recover from losing two straight for the first time all season? Can Wisconsin channel its consistency into sudden-death mode? And can St. Cloud State turn its back on its curious 0-forever NCAA record?

All are valid questions awaiting those four WCHA teams, all of which earned slots in this weekend’s NCAA regional hockey tournaments. At stake in the four regionals are opportunities to go to Detroit on April 8-10 to take part in the Frozen Four, in hopes of becoming the 37th WCHA team to win a national championship since the league was organized in 1951. It would, however, be the first WCHA national champ in four years, because, in a rarity, no WCHA team reached the final game the last three years.

The WCHA Final Five tournament is such a taxing and emotional event that perhaps it has become a challenge to maintain or reacquire momentum or flow from the Final Five to the NCAA tournament. This would seem to be the ideal opportunity for the WCHA to regain its stature, with four of the 16 NCAA entries.

The prime opportunity would seem to come in the West Regional at Xcel Center in St. Paul, where Wisconsin (25-10-4) is the No. 1 seed and will face No. 4 Vermont (17-14-7) in the 8 p.m. (CDT) Friday semifinal, after St. Cloud State (23-13-5) rides the No. 2 seed against No. 3 Northern Michigan 20-12-8) IN THE 4:30 game. Those winners meet Saturday at 8 p.m. for the West Regional title. An all-WCHA final, between Wisconsin and St. Cloud State, is certainly feasible, as the two teams are returning to the scene of the Final Five, where the Huskies topped the Badgers 2-0 in the semifinals.

League champion Denver (27-9-4) is the No. 1 seed in the East Regional at Albany, N.Y., where the Pioneers face Rochester Institute of Technology (26-11-1) at 2 p.m. Friday, followed by No. 2 seed Cornell (21-8-4) against No. 3 New Hampshire (17-13-7) in the 5:30 p.m. second game. Those winners will decide the Frozen Four entry at 5:30 p.m. Saturday.

Denver proved its superiority in winning the league title, behind goaltending champ Marc Cheverie, and league scoring champ Rhett Rakhshani, but the Pioneers have to try to get back in proper rhythm after losing both games — to North Dakota and Wisconsin — at the Final Five. Snapping back into form is not automatic.

North Dakota (25-12-5), riding a hot streak that includes a three-game surge to the Final Five’s Broadmoor Trophy, heads east also, where it will be the No. 2 seed in the Northeast Regional at Worcester, Mass., taking on No. 3 Yale (20-9-3) at 4 p.m. Saturday, preceded by a 12:30 p.m. match between No. 1 seeded Boston College (25-10-3) and fourth-seeded Alaska Fairbanks (18-11-9). Those winners collide Sunday at 4:30 p.m.

North Dakota is riding a hot streak of 12 victories in 13 games, with junior Evan Trupp contributing the latest hot hand. Trupp scored the clinching goal in the 2-0 victory over UMD to open the Final Five, then added two goals and assisted on the winner in the 4-3 victory over top-seeded Denver in the semifinals, and assisted on both goals when the Sioux countered from a 2-0 deficit against St. Cloud State and went on to a 5-3 victory for the Final Five title. Trupp, who came into the Final Five with 5-23–28, added 3-3–6 out of the first eight goals scored by the Sioux at Xcel Center.

The Midwest Regional at Fort Wayne, Ind., is the only one without a WCHA team, although it does have Bemidji State, which will be joining the WCHA next season. The Beavers (23-9-4) rate the No. 2 seed and will face Michigan (25-17-1) at 6:30 p.m. Saturday, following the 3 p.m. game between Miami of Ohio (27-7-7), the No. 1 seed overall, and No. 4 seed Alabama-Huntsville (12-17-3). Huntsville earned the slot after Niagara upset Bemidji State by beating Niagara in the College Hockey America final. That outcome, combined with Michigan’s upset of Miami and victory over Northern Michigan to win the CCHA’s automatic berth, conspired to bump Minnesota Duluth out of the 16-team field, or the WCHA would have had five entries.

An interesting aside is that Denver had never lost two games in succession all season, but was stung by North Dakota 4-3 in the WCHA semifinals, then also lost to Wisconsin 6-3 in the third-place game. The question facing the Pioneers is that those losses are meaningless if they regain their touch — unless they find it difficult to get back into their impressive form. It doesn’t help the Pioneers that Anthony Maiani, top scorer after the Rhett Rakhshani-Tyler Ruegsegger-Joe Colborne line, is out after being injured against North Dakota.

Wisconsin also has an impressive run of having not lost two in a row all season, a record the Badgers extended by beating Denver 6-3 in the third-place game after losing 2-0 to St. Cloud State in the semifinals of the WCHA Final Five. In that game, the Huskies lost Garrett Roe, their offensive co-leader with Ryan Lasch, when he slid into the boards trying to block a shot. Roe missed the 5-3 title loss to North Dakota, but will be back for the West Regional.

“He was more hurt than injured,” said St. Cloud State coach Bob Motzko after Thursday’s practice at Xcel Center. “He’ll be back, although he might have a sore neck.

“We’re playing well as a team, and we’re doing that the best we’ve done right now,” Motzko added. “I think we just have to keep chugging along. I’ve really liked our team from the start, and we’ve had a couple of good runs, and a couple of pops in the nose.”

The worst of those pops was an 8-1 loss to North Dakota in St. Cloud, but the Huskies responded by going to Wisconsin to win their next game 5-1. “We’ve had real battles through the playoffs,” Motzko said. “First we had to battle to beat Mankato in the best-of-three, then we had a great battle with Wisconsin, and then a great game against North Dakota.

“We went to Miami to open the season, and we lost two tough games, but we haven’t been swept since. When all else is equal, everything comes back to our penalty-killing. When we’re aggressive, we’re good killing penalties, but we gave up three poer-play goals against North Dakota. I’d have to say, though, that for 12-14 minutes of that game, North Dakota played great and put us back on our heels.”

The other thing the Huskies have going for them, when all else is equal, is the penchant for timely scoring from Roe and Lasch, both of whom have scored 19 goals, 27 assists, for 46 points. Penalty killing is vital, but so is the ability to generate scoring.

The Huskies also have something of a large hurdle to overcome, although Motzko points out that such history means nothing to the current crop of players. But this is the eighth time St. Cloud State has reached the NCAA tournament — third under Motzko — and the Huskies have yet to win their first regional game. It also is the first time the Huskies have been able to play in the West Regional, where the familiar Xcel Energy ice sheet should be surrounded by Huskies fans.

For now, Northern Michigan consumes the attention of Motzko and his Huskies. If they win, they can start worrying about Wisconsin — or Vermont. But that doesn’t prevent Motzko from seeing strong potential from WCHA teams at this year’s tournament.

“Our four teams that are in right now — all four — are playing their best right now,” said Motzko. “And I think any of the four have a good chance to win.”

John Gilbert is a lifetime Minnesotan and career journalist, specializing in cars and sports during and since spending 30 years at the Minneapolis Tribune, now the Star Tribune. More recently, he has continued translating the high-tech world of autos and sharing his passionate insights as a freelance writer/photographer/broadcaster. A member of the prestigious North American Car and Truck of the Year jury since 1993. John can be heard Monday-Friday from 9-11am on 610 KDAL(www.kdal610.com) on the "John Gilbert Show," and writes a column in the Duluth Reader.

John Gilbert is a lifetime Minnesotan and career journalist, specializing in cars and sports during and since spending 30 years at the Minneapolis Tribune, now the Star Tribune. More recently, he has continued translating the high-tech world of autos and sharing his passionate insights as a freelance writer/photographer/broadcaster. A member of the prestigious North American Car and Truck of the Year jury since 1993. John can be heard Monday-Friday from 9-11am on 610 KDAL(www.kdal610.com) on the "John Gilbert Show," and writes a column in the Duluth Reader.