Kenyan Emerges to Set Grandma’s Record

By John Gilbert

Dominic Ondoro was confident even back in the fog halfway through his first Grandma’s Marathon. Even then he was leading a swift pack of 11 East African runners that emerged almost mystically from the foggy North Shore and then disappeared again.

They were running at a pace that put them in reach of Dick Beardsley’s 33-year-old record time, but after consistently turning sub-5-minute miles, reaching the halfway point in 1:04:46, Ondoro and the group slowed down measurably, and it appeared once again the magical record would stand. It turned out to be a strategic move by Ondoro, who, wearing bib No. 1 and running easily in front, decided to slow down, just to see if he might coax one of his competitors to show his hand and make a break for the lead. Instead, the pack slowed down, too.

When the group slowed, did Ondoro think that he could still break the record? “Yes,” he said softly, after shattering the record with a 2 hour, 9 minute, 6 second performance.

With about seven miles to go, Ondoro took off like a Formula 1 race car whose driver just realized he had neglected to engage top gear. He pulled ahead, then pulled ahead more. Usually, when someone breaks from a group running that close together, at least a couple others stay reasonably close. Not this time.

When he ran up Lemon Drop Hill and sailed away down London Road, Ondoro got to the brick-covered area of Superior Street, at 5th Ave. E., he was running alone. There were the pace and media cars ahead of the field, and then one lone runner. When he disappeared onto West Superior Street, a look back to the east revealed nobody.

“I knew what the record was, and halfway through, I knew I could break the record,” Ondoro said. “I doubled my speed and nobody came with me.”

Beardsley, riding in his now-customary spot in one of the pace cars just ahead of the field, said someone called out to him: “Your record’s safe for another year.”

“Not the way he’s running,” Beardsley yelled back.

“I’ve never seen a nicer, smoother-looking runner,” Beardsley said afterward. “When they got to the 19.5 mile mark, there were still eight of them running together. But when he put the hammer down, nobody kept up with him. He looked back once, to see if anybody was close. Nobody was there. And he was running 2:29.5 miles there near the end.”

Ondoro is 26, which means he was seven years from being born in Eldoret, Kenya, when the greatest race in Grandma’s Marathon’s history was run, back in the event’s infancy. It was 1981, and defending Grandma’s champion Garry Bjorklund pushed Dick Beardsley to the limit before Beardsley persevered and covered the distance in 2 hours, 9 minutes, 37 seconds, blistering the 26.2-mile marathon from Two Harbors to Canal Park.

The record he broke had been set in 1980, one year before, by Bjorklund, whose winning time remained the event’s second-swiftest until Saturday. And Bjorklund’s second-best time behind Beardsley in 1981 was still the eighth best. Since then, for 32 consecutive years, several hundred of the best runners in the world have come to Duluth, filled with hope of breaking that record, only to leave with that stubborn 2:09:37 standard still standing.

But Dominic Ondoro came to the North Shore on Saturday, June 21, 2014 as a tall, lean man on a mission, and when he made his lengthy finishing surge, he reduced 10 strong competitors to an East African supporting cast. So dominant was Ondoro’s 2:09:06 time that when Betram Keter beat former Grandma’s winner Christopher Kipyego to the Canal Park finish line by a second to capture second place, they were almost three full minutes behind, at 2:11:58.

The straight chute ending with the abrupt rise at Lemon Drop Hill, which has undone so many worthy challengers over the years, was a speed bump to Ondoro. “I’m used to hills,” he said. “That’s the way I’m training. Eldoret is very hilly, in the mountains, so I’m used to this.”

Eldoret is a small village, and Ondoro and his family lived about two miles out of town, he estimated. He has run all his life, as a way of life, in Kenya. He had only run marathons for four years, but he has established his preference for running swiftly. In a little over a year, Ondoro won at Melbourne, Australia, with a 2:10.17 time, and he won last year at Tiberias, Israel, in an eye-popping 2:08.0.

“I liked the course,” Ondoro said. “I liked the fog, too. When I won at Melbourne, it was foggy like this.”

Beardsley Yields Record, but Can’t Erase Memory

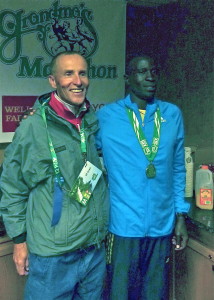

Dick Beardsley was quick to give Dominic Ondoro a congratulatory hug for breaking his record and winning the 38th Grandma’s Marathon, but there is no doubt that Beardsley’s amazing record run in 1981 will remain an iconic part of Grandma’s history.

Beardsley remembers details of that race as if they happened yesterday, instead of 33 years ago. And he was amazed when told that the track public address announcer proclaimed that the greatest thing about Beardsley’s victory was that “he did it all himself. He had nobody to help him.”

“Are you kidding?” Beardsley said, incredulously. “Garry Bjorklund pushed me all the way in that race, and there’s no way I would have set the record if he hadn’t.”

Garry Bjorklund from Twig was a local legend for his track and cross country running at Proctor High School and the University of Minnesota. Championship runners have a small window of opportunity to reach a true peak, and Bjorklund may have done it in 1979 and 1980, when he went to Boulder, Colo., to overload train in the high altitude for the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow. There are many, myself included, who believe that Bjorklund might have won the Olympic marathon in 1980, but that was the year that President Jimmy Carter, upset that the Soviet Union had invaded Afghanistan, decided to turn sports into the ultimate political gambit and forced the U.S. to bypass — boycott — the Moscow Olympics.

Bjorklund had to be torn up by the decision, because four years hence he would be past his prime. He came home to Duluth in June of 1980 and blistered the Grandma’s Marathon course to win in 2:10:20.

“I ran the 1980 Olympic trials, and Garry didn’t even run them,” Beardsley recalled. “He went to Duluth instead and ran a 2:10:20, and he did that all by himself.”

Beardsley also recalled that Bjorklund came back a bit out of shape to run the 1981 Grandma’s. “I had run a 2:08 at the Boston Marathon and finished second to Alberto Salazar in a race that came down to a 200-meter sprint,” Beardsley said. “At Grandma’s, there was one guy, one of the best, in Garry, the defending champion. A half-mile into the race, BJ — we all called Garry BJ — said to me, ‘I’m here for you, and I’ll help you any way I can, but it’s your race.’

“We stayed together all the way in, and just before the Lester River Bridge, I glanced back to see if anybody was coming, and when I turned back, Garry had made a surge, and got maybe 30 or 40 meters ahead of me. I kinda panicked. I caught up to him at about the 19-mile mark, and once I caught up to him, I figured I’ve got to make a statement, so I made a surge and put Garry about 10 meters back. A guy on a bike told me I had done a 4:42 mile, so I put on another surge and did a 4:36.

“That time, I could tell that BJ was hurting, but I though I was going to have a heart attack! I got to the top of Lemon Drop Hill, and glanced at my watch — but the battery had died. I had gotten a real bad side ache — a stitch in my right side — and I was praying the finish would come soon.

“When I got close to the Radisson, where we turn down off Superior Street onto 5th Avenue West, all of a sudden I see a little kid, right in the middle of the street, playing with a Tonka Toy truck. When I got to within about 15 meters of him, the kid gets up and starts to walk off, but at that moment, he looked at me and his eyes locked onto mine and he freezes. I tried to decide whether to go left or right, and I ran smack-dab into that little boy. I looked back and saw he was crying, and I thought, ‘Good. At least he’s breathing.’

“The best thing about that is my stitch went away. I came down to the finish and one of the neatest things about it was that my mom and dad, who never saw me run a marathon, were there in the final chute. My dad, who never showed any emotion, was jumping up and down. I finished at 2:09:36.6, and they rounded it up to 2:09:36.”

Still, Beardsley can’t look past Bjorklund’s performance. “Everyone talks about my 2:09, but Garry was second in 2:11,” Beardsley said. “He ran a better race than I did. He had taken some time off, and only had been training for six weeks.

“The most talented, gifted runner I’ve ever seen was BJ.”

Beardsley’s fondness for Duluth and Grandma’s remains, too, even now, while living in Austin, Texas. He says, though, that he and his wife are probably moving back to Minnesota from Texas, so he can be near the Detroit Lakes area, where he was a fishing guide for 30 years.

“Even though I’ve never lived in Duluth, I feel like it’s my second home,” Beardsley said. “I’ve been at a lot of marathons around the world, and my favorite event I come to is Grandma’s. All the people at the marathon and in Duluth have always treated me so well I hope to keep coming back.”

And no matter how many runners break his record how many times, Beardsley will forever be treated like the top ambassador for Grandma’s Marathon.

Ondoro Plans to Build School

It is a different world for marathon runners from Kenya. As they grow up, they run from home to school and back every day because there aren’t many roads, and there aren’t any parents waiting with the minivan running to drive them. One of the beautiful things about Dominic Ondoro winning Grandma’s Marathon is that he won about $30,000 and a new Toyota, or the monetary value of it, and one day later he was on a plane to return to his native Kenya, where he plans to spend some of the money helping to build a school for his hometown of Endoret.

His record-shattering time of 2:09:06 — 31 seconds under Dick Beardsley’s 33-year-old record — came one year after Sarah Kiptoo had broken the women’s record at Grandma’s with a 2:26:32. Kiptoo returned to race this year, but finished third, as Pasca Myers won at 2:33:45. Kiptoo said she wasn’t as motivated this year, but vowed to come back focused to reclaim Grandma’s title next June.

John Gilbert is a lifetime Minnesotan and career journalist, specializing in cars and sports during and since spending 30 years at the Minneapolis Tribune, now the Star Tribune. More recently, he has continued translating the high-tech world of autos and sharing his passionate insights as a freelance writer/photographer/broadcaster. A member of the prestigious North American Car and Truck of the Year jury since 1993. John can be heard Monday-Friday from 9-11am on 610 KDAL(www.kdal610.com) on the "John Gilbert Show," and writes a column in the Duluth Reader.

John Gilbert is a lifetime Minnesotan and career journalist, specializing in cars and sports during and since spending 30 years at the Minneapolis Tribune, now the Star Tribune. More recently, he has continued translating the high-tech world of autos and sharing his passionate insights as a freelance writer/photographer/broadcaster. A member of the prestigious North American Car and Truck of the Year jury since 1993. John can be heard Monday-Friday from 9-11am on 610 KDAL(www.kdal610.com) on the "John Gilbert Show," and writes a column in the Duluth Reader.