UMD had all the ingredients, plus magic

Kyle Schmidt raced down the ice, then slid feet-first after scoring the winning goal in UMD's first NCAA championship game.

By John Gilbert

How did they do it? How did this UMD men’s hockey team get itself gathered up to win its first-ever NCAA Division I hockey championship. All the right ingredients were there, without question, from speedy and high-scoring forwards to tough and agile defensemen, and on to clutch goaltending — but there were a dozen other teams that had those assets, too, and several of them were, frankly, playing better hockey down the stretch than the Bulldogs. How did it all come together?

Simple. It was “magic.”

That quality can be called a lot of things, from luck, to chemistry, to being a team of destiny. This season’s Bulldogs qualify for all of the above, but it’s easier to simply call it magic. That best explains how, at 3:22 of sudden-death overtime, a senior from Hermantown named Kyle Schmidt skated across in front of the Michigan net, from right to left, having spotted Travis Oleksuk, his centerman, behind the net with the puck. Oleksuk, who had scored earlier himself, passed it out front and in an instant, Schmidt had banged it past goaltender Shawn Hunwick and the demons of 50 years suddenly dissolved. “I saw it go in, and started skating for the other end,” said Schmidt.

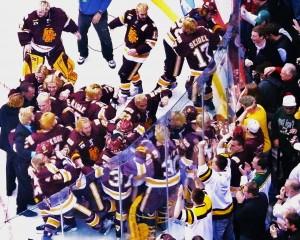

The 3-2 victory provided ended a great hockey game, and instead of waiting to be mobbed by his teammates, Schmidt raced down the ice, crossing the far blue line before he threw himself into a feet-first slide, as his teammates on the ice raced after him, only slightly ahead of the rest of the Bulldogs pouring off the bench. For a brief moment, Schmidt was sliding along, all alone, looking up at Xcel Energy Center’s rafters, above the seats filled with 19,222 screaming fans — alone with his magical moment, an isntant before being absolutely mobbed.

“It was amazing,” said Schmidt. “It’s great for the players, coaches, everyone here to win the championship, but I think it’s been ‘way too long coming, for everyone in Duluth, the Twin Ports, anyone Up North, and all UMD fans. To be around 50-some years and not have won it, but to have been so close back in ’84 — 27 years ago — and now to finally bring it home…It’s for everyone. It’s awesome.”

After 50 years of disappointment and frustration, the Bulldogs celebrate an NCAA men's championship.

It was even magical that Kyle Schmidt could summon up the image of the only other time a UMD team made it to the championship game, since he was three years from being born, in 1984. The four-overtime loss to Bowling Green remains a painful memory to all UMD fans who were alive at the time, and, perhaps surprisingly, remains a haunting heartbreak to the players on that team. You could almost feel the pain of that memory lifting as Schmidt went broad-sliding across Xcel Center’s ice surface.

Coach Scott Sandelin said he was speechless, in the post-game interview room. “When I came here 11 years ago, I left a team that won a national championship — actually, two in three years,” said Sandelin, recalling his time as an assistant at North Dakota. “I was willing to accept this challenge because, growing up in Hibbing, I believed you could win here. Sometimes you’ve got to go through some rough patches, and we have. We’ve had a staff that has worked hard, and we’ve recruited some great kids. There are so many good teams, but sometimes the chemistry and things have to go right. You have to get luck. And we certainly had the luck in overtime.”

Sandelin had his own recollection of UMD’s only previous NCAA final, because coach Mike Sertich’s Bulldogs beat North Dakota 3-2 in the semifinal in that 1984 tournament, and Sandelin was a North Dakota defenseman.

“The close call in 1984 comes back, but it stings the players more than me,” said Sertich, who coached UMD to that indelibly inscribed finish, and who returned home from the final step in a sequence of surgical procedures for blood clots that felled him in February, from last summer’s ankle surgery, just in time to see UMD’s 4-3 victory over Notre Dame in last Thursday’s semifinals. “I thought about it for a while, but there were other teams to coach, and I never realized how much it has stayed with guys like Tom Kurvers, and Mark Odnokon, or Norm Maciver, and Billy Watson.”

As a college student, I got serious about watching the UMD hockey program as sports editor of the UMD Statesman, back when they were in the MIAC, running up huge scores against all their opponents, while enjoying the unfair advantage of being able to play in the Curling Club, a wonderful place compared to the outdoor rinks of their competitors. I watched them make the bold move, under Ralph Romano, to Division I and enter the Western Collegiate Hockey Association, where they didn’t win much because they mostly were fighting for their hockey lives against super-powers from North Dakota, Michigan Tech, Denver, and Michigan, plus their good-ol’ Big Brothers from Minnesota. I was there when they opened the DECC and Huffer Christianson recorded a record six assists in an 8-1 debut game against the Gophers.

It took UMD awhile to build up to competitive speed, in the toughest league in the country. Bill Selman had some outstanding teams, and Gus Hendrickson laid the groundwork for his assistant, Mike Sertich, to take over and make his run at league titles in 1984 and 1985. It was the 1983-84 season that left the deepest wound. UMD had a wealth of players, led by the goaltender I rank best of all in Bulldog history — Rick Kosti. He was ably backed up by Jon Downing, but Kosti played 38 games in the 1983-84 season, with a record of 27-9-2 as UMD won its first WCHA championship. Kosti, incidentally, came back and played a school record 45 games the next season, going 33-9-3 for the most wins in a season for any goaltender, as UMD won the title again. Kosti’s 60 career victories are the most for any goalie in UMD history, and he only played two seasons — both WCHA championship seasons, the only ones in UMD history, until the Derek Plante-led Bulldogs won it again in 1992-93.

Forwards on that 1983-84 team included Bill Watson, Mark Odnokon, Skeeter Moore, Mark Baron, Tom Herzig, Bob Lakso, Matt Christensen, Jim Toninato, Sean Toomey, Bruce Fishback, Brian Durand, and Brian Johnson, and the defense was led by Tom Kurvers, Norm Maciver, Jimmie Johnson, Guy Gosselin, Bill Grillo, and Jim Plankers. To know how those players measured up with the rest of the country, consider that Watson scored 35-51–86 that season, numbers he eclipsed a year later with 49-60–109 — UMD’s record for assists and points in a season. Kurvers, meanwhile, as senior captain in 1983-84, scored 18-58–76 from defense, records for assists and points by a defenseman in a season, and he went on to record the most career points for a defenseman at 192 for his four years. Maciver, another magician with the puck, broke Kurvers’ record for most career assists by a defenseman a couple years later with a four-year total of 152. That group of Bulldogs also claimed successive Hobey Baker Awards, with Kurvers winning in 1984 and Watson in 1985.

College hockey is a different world now, but that 1983-84 team was special. Ralph Romano, who coached the first D1 UMD teams before devoting all his time to being athletic director, had suffered a heart attack at a midseason game against Denver, and died. The team carried on, dedicating the rest of the chase to Romano. I had the opportunity to travel to Lake Placid, where I had been for the 1980 Olympics, and this time could enjoy covering UMD — “Minnesota’s Team” — for the Minneapolis Tribune. We rode out on the UMD-commissioned charter flight. The Bulldogs beat North Dakota on Watson’s overtime goal in the semifinals. “People forget that North Dakota had a goaltender named Jon Casey that year,” said Sertich. The next day, Kurvers was named UMD’s first Hobey winner.

Surely, Bowling Green couldn’t cope with this arsenal, although as a fairly objective reporter, no assumptions were made. UMD was cruising along, leading 4-2, but in the Olympic Arena press box, there was no deja vu about 1980. When the U.S. beat the Soviet Union and went on to Olympic Gold, it was truly the Miracle on Ice; this time, the Bulldogs were the best, ranked No. 1 in the country, and they were headed for UMD’s first NCAA title with just about the same amount of “favorite” as the Soviets had in 1980. Oops.

Bowling Green got a goal, closing it to 4-3. That made it tense, for sure, but UMD played it sure-handed, backing off from its prefered attack mode to ride out the closing minutes, as they ticked down to only a couple. A Bowling Green player, unable to attack, threw the puck up the right boards and into the UMD zone. Routinely, Kosti went behind the goal to tee it up for his defensemen. As he got to the end boards, the puck hit a seam in the right-corner boards and the puck glanced crazily directly out to the slot. Before Kosti could react, a Bowling Green skater rapped the puck into the unguarded goal, and it was 4-4. “It was funny, because being there and watching it, there was more of a feeling of disbelief,” said Sertich. “Did I just see what happened? I was more shocked than anything.”

Because UMD had never won an NCAA title, there was still a feeling of unproven underdogs. “No question, the teams that had a tradition of winning national championships play with a little swagger, compared to being awe-struck, the way other teams are,” said Sertich. It wasn’t awe, by then in that championship game, just uncertainty, which swept through the press box like a fog rolling off Lake Superior. It created a hollow feeling, as the teams battled through overtime, because the certainty that the Bulldogs were headed for the national championship was replaced by a sincere hope that they could still prevail. The uncertainty grew through a second overtime, then a third. In the fourth, fatigue was becoming obvious, but suddenly Bowling Green scored. The game was over, and Bowling Green had won 5-4 in four overtimes. Rick Kosti had made 55 saves.

The next year, UMD again won the WCHA and again was the favorite going into Detroit for the Frozen Four, which was “allowed” to be called the Final Four back then.. The Bulldogs faced RPI in the semifinal, and while Kurvers was gone, a new player named Brett Hull had shown up, and Kosti set his record, Watson scored enough to win the Hobey, and surely no ECAC team was going to derail the Bulldogs. But RPI did it, in three overtimes. That left the 1984 team as the only one to get to the final, although the run of great success convinced UMD fans that it would be just a matter of time until one of these great teams would break through.

Bill Watson is now a volunteer assistant coach with the Bulldogs. Tom Kurvers and Norm Maciver work in player personnel and scouting with NHL teams. During the playoffs, it was fun to talk to Kurvers and Maciver about the Bulldogs. They agreed that the greatest natural leader of any Bulldog team was Odnokon — “Ozzie” — who was a forceful winger and a dominant personality. Sertich recalled that on one of his teams, they had a miserable practice after returning to the ice from holiday break. “I lined ’em up and said, ‘Anybody who was NOT out late last night, step forward,’ and nobody did,” said Sertich. “I didn’t realize until later that Odnokon had told the team that they were all going out together, and everyone did. That’s the power he had.”

Flash forward 27 years now, to the Xcel Center press box. Just before the final game was to start, the fellow directing media at the press box entrance came and summoned me because a couple fellows wanted to talk to me. I went out by the elevators, and there they were — Kurvers and Odnokon. We talked for about 5 minutes, then they had to head for their seats. It was one of those sessions where I think they were burning off a little nervous energy, maybe trying to carve through a little of that 27-year-old hangover.

As I returned to my seat, I spotted Kevin Pates, an always-friendly reporter from the Duluth News-Tribune, who’s been covering the Bulldogs for years. I told him I wish I had come and gotten him, because he would have enjoyed saying hello to Kurvers and Odnokon. Pates, who is a diminutive fellow, smiled, and recalled instantly back in that 1983-84 season when Kurvers and Odnokon stopped by his hotel room, allegedly to talk. “They wrapped me up in a blanket, and stuffed me into the shower,” Pates said. Sertich got a laugh out of that: “They ‘mummied’ him,” he said.

If you were betting on it, if you knew that UMD’s mighty first line would be harnessed all night and not only fail to score a goal at even strength or on the power play, and would, in fact, be outscored by Bill Winnett from Michigan’s checking line, you wouldn’t give UMD much of a chance. And if you knew that Michigan would also get a goal to tie the game 2-2 from fourth-line center Jeff Rohrkemper, the odds would slip further. And if you knew the game would broil on into sudden-death overtime, you might have trouble with the realization that just a month earlier, Duluth East and Hermantown had come to the state high school tournament on the same Xcel Energy Center rink, and East in Class AA and Hermantown in Class A both lost — in overtime.

But the Bulldogs got to that overtime by having invented other ways to survive. Travis Oleksuk, junior center on the second line, scored one goal, lifting UMD to a 1-1 tie early in the second period. A few minutes later, Max Tardy, a little-used but highly-skilled freshman from Duluth East, who had been inserted as fourth-line center just before the playoffs, came out on the second power-play unit and scored his first collegiate goal for a 2-1 UMD lead. Michigan tied the game 2-2 later in the second period, and the scoreless third period ended, signalling overtime, and undoubtedly signalling a collective sinking feeling among UMD’s veteran fans. Not again. Not another excruciating, wrenching close call to be snuffed in overtime.

Here’s Michigan, full of high-tempo swagger in pursuit of its 10th NCAA title, and there were the Bulldogs, with no tradition of winning national championships in their arsenal. Time for more magic. Schmidt, whose injury during the East Regional gave coach Scott Sandelin the idea to put Tardy on the second power-play unit as a replacement, had just won the college hockey commissioner’s award as the nation’s unsung hero for the season. It is an award that goes to a hard-working and honest player, but definitely to someone who has managed to play well while avoiding being the guy in the spotlight.

It was Kyle Schmidt, a senior from Hermantown, who spotted Oleksuk’s move behind the net, and went for the slot, and who banged in Oleksuk’s pass. It was a quick, stunning goal. A one-timer, in more ways than one. It sent Schmidt racing to the far end of the rink, to his broadslide that could have been the aftermath of ESPN’s Play of the Day. The goal gave UMD its eighth victory in overtime this season, its first NCAA championship ever, and with the power to eliminate all those demons from 27 years ago, to say nothing of a proper way to celebrate 50 years of Division I hockey. After the game, Kurvers and Odnokon were down at the UMD dressing room, where they could join Watson. The current Bulldogs brought out their trophy, so that Kurvers and Odnokon could heft it for a magical moment.

To win a championship, it takes skill, determination, strong skating, hitting, defense, goaltending, and a tenacious and resilient character. But all of those ingredients can’t do it alone. They also need a little magic.

Comments

Tell me what you're thinking...

and oh, if you want a pic to show with your comment, go get a gravatar!

John Gilbert is a lifetime Minnesotan and career journalist, specializing in cars and sports during and since spending 30 years at the Minneapolis Tribune, now the Star Tribune. More recently, he has continued translating the high-tech world of autos and sharing his passionate insights as a freelance writer/photographer/broadcaster. A member of the prestigious North American Car and Truck of the Year jury since 1993. John can be heard Monday-Friday from 9-11am on 610 KDAL(www.kdal610.com) on the "John Gilbert Show," and writes a column in the Duluth Reader.

John Gilbert is a lifetime Minnesotan and career journalist, specializing in cars and sports during and since spending 30 years at the Minneapolis Tribune, now the Star Tribune. More recently, he has continued translating the high-tech world of autos and sharing his passionate insights as a freelance writer/photographer/broadcaster. A member of the prestigious North American Car and Truck of the Year jury since 1993. John can be heard Monday-Friday from 9-11am on 610 KDAL(www.kdal610.com) on the "John Gilbert Show," and writes a column in the Duluth Reader.